Notes from Underground

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 15:11, 19 June 2015 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 15:14, 19 June 2015 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) Next diff → |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| <hr> | <hr> | ||

| "It was not only that I could not become spiteful, I did not know how to become anything; neither spiteful nor kind, neither a rascal nor an honest man, neither a hero nor an insect. Now, I am living out my life in my corner, taunting myself with the spiteful and useless consolation that an intelligent man cannot become anything seriously, and it is only the fool who becomes anything." | "It was not only that I could not become spiteful, I did not know how to become anything; neither spiteful nor kind, neither a rascal nor an honest man, neither a hero nor an insect. Now, I am living out my life in my corner, taunting myself with the spiteful and useless consolation that an intelligent man cannot become anything seriously, and it is only the fool who becomes anything." | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "You believe in a palace of crystal that can never be destroyed--a palace at which one will not be able to put out one's tongue or make a long nose on the sly. And perhaps that is just why I am afraid of this edifice, that it is of crystal and can never be destroyed and that one cannot put one's tongue out at it even on the sly." | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

Revision as of 15:14, 19 June 2015

| "I am a sick man. ... I am a spiteful man"

"It was not only that I could not become spiteful, I did not know how to become anything; neither spiteful nor kind, neither a rascal nor an honest man, neither a hero nor an insect. Now, I am living out my life in my corner, taunting myself with the spiteful and useless consolation that an intelligent man cannot become anything seriously, and it is only the fool who becomes anything." "You believe in a palace of crystal that can never be destroyed--a palace at which one will not be able to put out one's tongue or make a long nose on the sly. And perhaps that is just why I am afraid of this edifice, that it is of crystal and can never be destroyed and that one cannot put one's tongue out at it even on the sly." |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

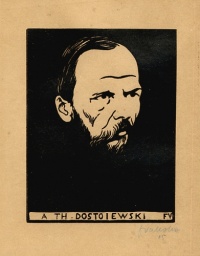

Notes from Underground, also translated in English as Notes from the Underground or Letters from the Underworld) (1864) is a short novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Often called the world's first existentialist work, it presents itself as an excerpt from the rambling memoirs of a bitter, isolated, unnamed narrator (generally referred to by critics as the Underground Man) who is a retired civil servant living in St. Petersburg.

Plot summary

The novel is divided into two rough parts. Part 1 falls into three main sections. The short introduction propounds a number of riddles whose meanings will be further developed. Sections two, three and four deal with suffering and the enjoyment of suffering; sections five and six with intellectual and moral vacillation and with conscious "inertia"-inaction; sections seven through nine with theories of reason and advantage; the last two sections are a summary and a transition into Part 2. Part 1 focuses primarily on man's desire to distinguish himself from nature (not "nature" in the sense of animals, trees, the natural world, but rather to point out flaws in thinking that there are "natural laws" which govern the way man must behave.) The narrator describes this as his spitefulness. It is elaborated into not only a spitefulness for authority and morality, but for causality itself. War is described as people's rebellion against the assumption that everything needs to happen for a purpose, because humans do things without purpose, and this is what determines human history. Secondly, the narrator's desire for pain and paranoia (which parallels Raskolnikov's behavior in Crime and Punishment) is exemplified in a tooth ache, which he says human beings only moan about to spread their suffering to others due to the cruelty of society (and he desires to have one), and paranoia which he builds up in his head to the point he is incapable of looking his co-workers in the eye. The main issue is that the underground man has reached a point of inactivity. Unlike most people, who typically act out of revenge because they believe justice is the end, he is conscious of this problem. Because of this, though he feels the desire for revenge, he is unable to complete it and thus his feelings of spite are given rise because he is simply left to feel guilt at even thinking of revenge. He feels that others like him exist, yet he continuously concentrates on his spitefulness instead of on action that avoids the problems he is so concerned with. He even admits at one point that he’d rather be inactive out of laziness. The first section also gives a harsh criticism of determinism and humanity’s movement towards attempting at outlining human action, which the underground man mentions in terms of a simple math problem (2+2=4). He states that despite humanity’s attempt to create the Crystal Palace (a reference to a famous symbol in Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s What Is to Be Done?), it cannot avoid the simple fact that anyone at any time can decide to act against what is considered good, simply to state one’s existence.

The second part is the actual story proper and consists of three main segments that lead to a furthering of the underground man’s super-consciousness. The first is his obsession with an officer who moves him out of position like a piece of furniture at a bar. He sees the man on the streets and thinks of ways to get his revenge, eventually deciding to bump into him, which he does, to find, to his surprise, that the officer does not seem to even notice it happened. The second segment is a dinner party with some old school friends to wish Zverkov goodbye as he leaves for the service. The underground man hated them when he was younger, but after a random visit to Simonov’s he decides to meet them at the appointed location. They forget to tell him that the time has been changed to six instead of five, so he arrives early. He gets into an argument with the three after a short time, declaring all of his hatred of society and using them as the symbol of it. At the end they go off without him to a secret brothel, and in his rage later that evening the underground man goes there to confront Zverkov once and for all, regardless if he is beaten or not. It is there that he meets and has sex with Liza, a young prostitute. He wakes up and the third segment begins. After sitting in silence for awhile, the underground man confronts Liza, who is unwavering at first, but eventually realizes the plight of her position and how she will slowly become useless and go lower and lower until she is no longer wanted by anyone. The thought of dying such a terribly disgraceful death brings her to realize her position, and she then finds herself enthralled by the underground man’s seemingly poignant grasp of society’s ills. He gives her his address and leaves. After this, he is overcome by the fear of her actually arriving at his dilapidated apartment, and in the middle of an argument with his servant, she arrives. He then curses her and takes back everything he said to her, saying he was in fact laughing at her and reiterates the truth of her miserable position. Near the end of his painful rage he wells up in tears after saying that he was only seeking to have power over her and a desire to humiliate her. He begins to criticize himself and states that he is in fact horrified by his own poverty and embarrassed by his situation. Liza realizes how pitiful he is and they embrace. The underground man cries out “They – they won’t let me – I – I can’t be good!” After this he still acts terribly towards her and before she leaves he stuffs something into her hand, which she throws onto the table. It was a five ruble note. He tries to catch her as she goes out onto the street but cannot find her and never hears from her again. He recalls this moment as making him unhappy whenever he thinks of it, yet again proving the fact from the first section that his spite for society and his inability to act like it makes him unable to act better than it.

Literary significance & criticism

The Underground Man became a common character type in many of the works that followed the novella. He is present in Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina in the milder form of the character Nikolai Levin, in Anton Chekhov's Ward No. 6, Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, and in Joseph Heller's Catch-22 as Yossarian the 28-year-old Army Air Corps Captain.

Like many of Dostoevsky's novels, Notes from Underground was unpopular with Soviet literary critics due to its explicit rejection of socialist utopianism and its portrait of humans as irrational, uncontrollable, and uncooperative. His claim that human needs can never be satisfied even through technological progress, also goes against Marxist beliefs. Many existentialist critics, notably Jean-Paul Sartre, considered the novel to be a forerunner of existentialist thought and an inspiration to their own philosophies.

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was very impressed with Dostoevsky, claiming that "Dostoevsky is one of the few psychologists from whom I have learned something," and that Notes from Underground "cried truth from the blood".

The novel has also been cited by Paul Schrader as an influence when he wrote the screenplay for the film Taxi Driver, which has existential themes. The film actually quotes Dosteovsky in the line: "I'm God's lonely man."

Oleg Liptsin has adapted Notes from Underground for the stage. The world premiere was at the Phoenix Theatre in San Francisco on September 28th, 2007.

The novel American Psycho quotes a passage from 'Notes from Underground'.

In music, the Manchester post-punk group Magazine recorded the track "Song From Under the Floorboards", inspired by the book's themes, and based on the more literal translation of the book's title from the original Russian.

See also