Crime and Punishment

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"Legislators and leaders of men, such as Lycurgus, Solon, Mahomet, Napoleon, and so on, were all without exception criminals, from the very fact that, making a new law they transgressed the ancient one, handed down from their ancestors and held sacred by the people, and they did not stop short at bloodshed either, if that bloodshed often of innocent persons fighting bravely in defence of ancient law were of use to their cause." -- Rodion Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky "The similarities between Dostoyevsky's 'extraordinary man' and Nietzsche's ubermensch in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, published seventeen years later are striking. However Walter Kaufmann confirmed in 1974 that Nietzsche did not read Dostoyevsky until after he wrote Zarathustra." --Sholem Stein |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

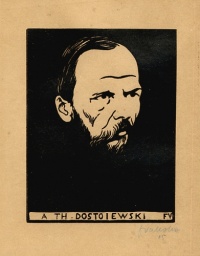

Crime and Punishment (1867) is a novel by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky, that was first published in the literary journal The Russian Messenger in twelve monthly installments in 1866, and was later published in a single volume. Robert Bresson's Pickpocket is a loose adaptation of the novel which substitutes murder with the crime of pickpocketing.

Contents |

Synopsis

Crime and Punishment focuses on the mental anguish and moral dilemmas of Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov, an impoverished St. Petersburg student who formulates and executes a plan to kill a hated, unscrupulous pawnbroker for her money, thereby solving his financial problems and at the same time, he argues, ridding the world of evil.

Story

Raskolnikov, a student, chooses to live in a tiny, rented room in Saint Petersburg. He refuses all help, even from his friend Razumikhin, and plans to murder an old-woman money-lender, Alëna, and profit from her wealth—his motivation, whether personal or ideological, remains unclear. When Raskolnikov kills Alëna, however, he is also forced to kill her half-sister, Liza, who happens to enter the scene of the crime.

After the bungled murder Raskolnikov falls into a feverish state. He behaves as though he wishes to betray himself, and the detective Porfiry begins to suspect him purely on psychological grounds. At the same time, a chaste relationship develops between Raskolnikov and Sonia—a prostitute full of Christian virtue, driven into the profession by the habits of her father—and Raskolnikov confesses his crime to her. The confession is overheard by Svidrigaylov, a shadowy figure whose aim is to seduce Raskolnikov's sister, Dunya. Svidrigaylov appears to have a hold over Raskolnikov, but when he unexpectedly commits suicide, Raskolnikov goes to the police himself to confess. He is sentenced to penal servitude in Siberia; Sonia follows him, and the Epilogue holds out hope for Raskolnikov's redemption and moral regeneration under her influence.

Themes

Dostoevsky's letter to Katkov reveals his immediate inspiration, to which he remained faithful even after his original plan evolved into a much more ambitious creation: a desire to counteract what he regarded as nefarious consequences arising from the doctrines of Russian nihilism.In the novel, Dostoevsky pinpointed the dangers of both utilitarianism and rationalism, the main ideas of which inspired the radicals, continuing a fierce criticism he had already started with his Notes from Underground. A Slavophile religious believer, Dostoevsky utilized the characters, dialogue and narrative in Crime and Punishment to articulate an argument against westernizing ideas in general. He thus attacked a peculiar Russian blend of French utopian socialism and Benthamite utilitarianism, which had led to what radical leaders, such as Nikolai Chernyshevsky, called "rational egoism".

The radicals refused however to recognize themselves in the novel's pages (Dimitri Pisarev ridiculed the notion that Raskolnikov's ideas could be identified with those of the radicals of his time), since Dostoevsky portrayed nihilistic ideas to their most extreme consequences. The aim of these ideas was altruistic and humanitarian, but these aims were to be achieved by relying on reason and suppressing entirely the spontaneous outflow of Christian pity and compassion. Chernyshevsky's utilitarian ethic proposed that thought and will in man were subject to the laws of physical science. Dostoevsky believed that such ideas limited man to a product of physics, chemistry and biology, negating spontaneous emotional responses. In its latest variety of Bazarovism, Russian nihilism encouraged the creation of an élite of superior individuals to whom the hopes of the future were to be entrusted.

Raskolnikov exemplifies all the potentially disastrous hazards contained in such an ideal. Frank notes that "the moral-psychological traits of his character incorporate this antinomy between instinctive kindness, sympathy, and pity on the one hand and, on the other, a proud and idealistic egoism that has become perverted into a contemptuous disdain for the submissive herd". Raskolnikov's inner conflict in the opening section of the novel results in a utilitarian-altruistic justification for the proposed crime: why not kill a wretched and "useless" old moneylender to alleviate the human misery? Dostoevsky wants to show that this utilitarian type of reasoning and its conclusions had become widespread and commonplace; they were by no means the solitary invention of Raskolnikov's tormented and disordered mind. Such radical and utilitarian ideas act to reinforce the innate egoism of Raskonikov's character, and to turn him into a hater rather than a lover of his fellow humans. He even becomes fascinated with the majestic image of a Napoleonic personality who, in the interests of a higher social good, believes that he possesses a moral right to kill. Indeed, his "Napoleon-like" plan drags him to a well-calculated murder, the ultimate conclusion of his self-deception with utilitarianism.

In his depiction of the Petersburg background, Dostoevsky accentuates the squalor and human wretchedness that pass before Raskolnikov's eyes. He also uses Raskolnikov's encounter with Marmeladov to present both the heartlessness of Raskolnikov's convictions and the alternative set of values to be set against them. Dostoevsky believes that the "freedom" propounded by the aforementioned ideas is a dreadful freedom "that is contained by no values, because it is before values". The product of this "freedom", Raskolnikov, is in perpetual revolt against society, himself, and God. He thinks that he is self-sufficient and self-contained, but at the end "his boundless self-confidence must disappear in the face of what is greater than himself, and his self-fabricated justification must humble itself before the higher justice of God". Dostoevsky calls for the regeneration and renewal of the "sick" Russian society through the re-discovering of their country, their religion, and their roots.

Film adaptations

There have been many film adaptations of the novel. Some of the best-known are:

- Crime and Punishment (1935, starring Peter Lorre, Edward Arnold and Marian Marsh)

- Crime et Châtiment (1956, France directed by Georges Lampin, starring Lino Ventura and Jean Gabin)

- Eigoban Tsumi to Batsu (1953, manga by Tezuka Osamu, under his interpretation)

- Преступление и наказание (USSR, 1969, starring Georgi Taratorkin, Tatyana Bedova, Victoria Fyodorova) [1]

- Crime and Punishment (1979, television serial starring Timothy West, Vanessa Redgrave and John Hurt)

- Aki Kaurismäki's Rikos ja Rangaistus (1983; Crime and Punishment), the acclaimed debut film of the Finnish director with Markku Toikka in the lead role; the story is set in modern-day Helsinki.

- Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment (1998, a TV movie starring Patrick Dempsey, Ben Kingsley and Julie Delpy)

- Crime and Punishment in Suburbia (2000, an adaptation set in modern America and "loosely based" on the novel)

- Crime and Punishment (2002, starring Crispin Glover, John Hurt, Vanessa Redgrave and Margot Kidder).

- Crime and Punishment another television serial (2002, starring John Simm as Raskolnikov and Ian McDiarmid as Petrovich)

See also