Fantastic

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 20:01, 11 July 2022 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| | style="text-align: left;" | | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| - | "They did not indeed relinquish the things in which they had delighted during the epoch in which [[van Eyck]] dominated northern art. After engravers of the fifteenth century, [[Schongauer]] and the master who signs himself [[E. S.]], had begun to represent scenes from everyday life, such themes were now made subjects of pictures. After van Eyck had carefully painted every bud and leaf, and [[Goes]] and [[Memling]] had followed with real landscapes as backgrounds, the study of [[landscape painting]] as an independent branch was now begun. In addition to this, painting mastered a third domain: [[the fantastic]]. As long as the spirit of realism prevailed, artists had painted only what they saw, looking with suspicious eye upon anything beyond this. But when, in consequence of the ecclesiastical reaction, metaphysical tendencies followed the realistic, the fantastic element at once appeared. It was developed to an even greater extent in the North than in Italy, because the fantastic is a more important element in the northern than in the Italian character. The art of engraving, which, with greater facility than the brush, follows the spirit into the world of [[fable]], became of determinative importance. After Schongauer in his ''[[Temptation of St. Antony]]'' had first modestly entered the territory the artists who followed him took possession of the entire legendary domain. "--''[[The History of Painting: From the Fourth to the Early Nineteenth Century]]'' (1893/94) by Richard Muther | ||

| - | <hr> | ||

| "On a general level, the concept of [[fantastic]] is [[ambiguous]] because it can mean [[greatness]] as well as a certain sensibility in the arts, where it is used to denote works which defy [[natural laws]] and traditional ideas of reality. In the [[visual arts]] it has been always important but it came especially to the fore in [[mannerism]], [[Romanticism]], [[Symbolism]], [[Decadent movement]] and [[Surrealism]]. | "On a general level, the concept of [[fantastic]] is [[ambiguous]] because it can mean [[greatness]] as well as a certain sensibility in the arts, where it is used to denote works which defy [[natural laws]] and traditional ideas of reality. In the [[visual arts]] it has been always important but it came especially to the fore in [[mannerism]], [[Romanticism]], [[Symbolism]], [[Decadent movement]] and [[Surrealism]]. | ||

Current revision

|

"On a general level, the concept of fantastic is ambiguous because it can mean greatness as well as a certain sensibility in the arts, where it is used to denote works which defy natural laws and traditional ideas of reality. In the visual arts it has been always important but it came especially to the fore in mannerism, Romanticism, Symbolism, Decadent movement and Surrealism. Our ultimate aim is to reconcile the concepts of the uncanny, Das Unheimliche and the fantastic. The irony is of course that since some time, the word fantastique has been introduced in the English language. The benefit of the term fantastique is that it does not necessarily have the connotation of greatness which is linked with the word fantastic. Another irony is that the Germans have started using the term fantastik. In short, the fantastic as genre is the most complex area of research in genre theory, because of its universal presence and multi-language confusion. A great deal of literature, from every part of the world and dating back to time immemorial, falls within the category of fantastic. Fairy tales like The Book of One Thousand and One Nights and epic literature like the Romance of the Holy Grail are within the scope of this genre."--Sholem Stein |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

The fantastic is a term in narratology and the visual arts. It refers to fantasy.

Contents |

Etymology

Borrowed from Middle French fantastique, from Late Latin phantasticus, from Ancient Greek φᾰντᾰστῐκός (phantastikós, “imaginary, fantastic; fictional”), from Φαίνω, ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *bʰeh₂- (“to shine”). Doublet of fantastique.

Fantastic literature

Fantastic literature, fantastic fiction or fantastic tales is a literary genre. A great deal of literature, from every part of the world and dating back to time immemorial, falls within the category of fantastic. Fairy tales like The Book of One Thousand and One Nights and epic literature like the Romance of the Holy Grail are within the scope of this genre.

Fantastic as a literary term was originated in the structuralist theory of critic Tzvetan Todorov in his 1970 treatise The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Todorov describes the fantastic as being a liminal state of the supernatural. A truly fantastic work is subtle in the working of the feeling, and would leave the reader with a sense of confusion about the work, and whether or not the phenomenon was real or imagined. Tzvetan Todorov holds that fantastic literature involves an unresolved hesitation between a supernatural (or otherwise paranormal or impossible) solution and a psychological (or realistic) one. His term hesitation is reminiscent of the terms ambiguity and ambivalence used in the definition of the grotesque.

Todorov compares the fantastic with two other ideas: The Uncanny, wherein the phenomenon turns out to have a rational explanation such as in the gothic works of Ann Radcliffe; or the marvelous, where there truly is a supernatural explanation for the phenomenon.

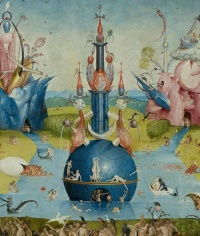

Fantastic art

Fantastic art is an art genre. The parameters of fantastic art have been tentatively defined in the scholarship on the subject ever since the 19th century. However, the genre had to wait for the inter war period to be mentioned by name at the "Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism" exhibition of winter 1936/1937 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which displayed pre-surrealist works such as The Titan's Goblet by Thomas Cole.

Fantasy has been an integral part of art since its beginnings, but has been particularly important in mannerism, magic realist painting, romantic art, symbolism, surrealism and lowbrow. In French, the genre is called le fantastique, in English it is sometimes referred to as visionary art, grotesque art or mannerist art. It has had a deep and circular interaction with fantasy literature.

Fantastic art explores fantasy, "space fantasy" (a sub-genre which incorporates subjects of alien mythology and/or alien religion), imagination, the dream state, the grotesque, visions and the uncanny, as well as so-called "Goth" art. Being an inherent genre of Victorian Symbolism, modern fantastic art often shares its choice of themes such as mythology, occultism and mysticism, or lore and folklore, and generally seeks to depict the [inner life] (nature of soul and spirit).

Fantastic art should not be confused with fantasy art, which is the domain of science-fiction and fantasy illustrators such as Boris Vallejo and others.

Fantastique

The Fantastique is a French term for a literary and cinematic genre that overlaps with science fiction, horror and fantasy.

The fantastique is a substantial genre within French literature. Arguably dating back further than English fantasy, it remains an active and productive genre which has evolved in conjunction with anglophone fantasy and horror and other French and world literature. In French criticism, the term was first widely used to describe the work of German Romanticism, especially E.T.A. Hoffmann, after Jean-Jacques Ampère's 1829 translation of Hoffmann's Fantasy Pieces in the Manner of Callot (1814).

Bibliography of the 'fantastic'

- Das Unheimliche (1919) / The Uncanny - Sigmund Freud

- The Romantic Agony (Italy, 1930) - Mario Praz

- Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (1936) exhibition catalogue by Alfred Barr and Georges Hugnet

- Le moyen âge fantastique (Paris, 1955) Jurgis Baltrušaitis

- The Grotesque in Art and Literature (1957) - Wolfgang Kayser

- Arts fantastiques (Paris, 1960) - Claude Roy

- L'Art et la littérature fantastiques (1960) - Louis Vax

- L'Art fantastique (1961) - Marcel Brion

- La séduction de l'étrange. Étude sur la littérature fantastique (1964) - Louis Vax

- Au coeur du fantastique (Paris, 1965) - Roger Caillois

- Dreamers of Decadence: Symbolist Painters of the 1890s (1969) by Philippe Jullian

- Introduction à la littérature fantastique (1970) / The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre - Tzvetan Todorov

- 200 Jahre Phantastische Malerei (Berlin, 1973) - Wieland Schmied

- Zauber Der Medusa: Europaische Manierismen (1987) by Werner Hofmann

- The Occult in Art (1990) - Owen S. Rachleff

- Les peintres du fantastique (1996) - André Barret

Notes: nature and scope of the fantastic as genre

On a semantic level, the term fantastic is ambiguous because it can mean greatness as well as a certain sensibility in the arts, where it is used to denote works which defy natural laws and traditional ideas of reality. In the visual arts this sensibility has been always important but it came especially to the fore in Mannerism, Romanticism, Symbolism, the Decadent movement and Surrealism.

The ultimate aim of this wiki is to reconcile the concepts of the uncanny, Das Unheimliche and the fantastic.

See also