Miguel de Cervantes

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"Cervantes entered into rivalry with makers of the picaresque when in Don Quixote he drew a memorable rascal, Ginés de Pasamonte, whose autobiography, he declared, if ever written, should excel Lazarillo's and Guzman's. In the delightful Novelas Exemplares (1613) he further told such tales of roguery as Rinconete y Cortadillo, La ilustre fregona, El casamiento engañoso, and the El coloquio de los perros, and several of his pieces for the stage — notably the Rufian Dichoso and the farce Pedro de Urdemalas — proved their kinship with the genre."--The Literature of Roguery (1907) by Frank Wadleigh Chandler |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Don Miguel de Cervantes y Saavedra September 29, 1547 – April 23, 1616) was a Spanish novelist, poet, and playwright, best-known as writer of Don Quixote.

Contents |

Cervantes' historical importance and influence

Cervantes' novel Don Quixote has had a tremendous influence on the development of prose fiction. It has been translated into all major languages and has appeared in 700 editions. The first translation was in English, made by Thomas Shelton in 1608, but not published until 1612. Shakespeare had evidently read Don Quixote, but it is most unlikely that Cervantes had ever heard of Shakespeare. Carlos Fuentes raised the possibility that Cervantes and Shakespeare were the same person (see Shakespearean authorship question). Francis Carr has suggested that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare's plays and Don Quixote.

Don Quixote has been the subject of a variety of works in other fields of art, including operas by the Italian composer Giovanni Paisiello, the French Jules Massenet, and the Spanish Manuel de Falla, a Russian ballet by the Russian-German composer Ludwig Minkus, a tone poem by the German composer Richard Strauss, a German film (1933) directed by G. W. Pabst, a Soviet film (1957) directed by Grigori Kozintsev, a 1965 ballet (no relation to the one by Minkus) with choreography by George Balanchine, and the American musical Man of La Mancha (1965), made into a film in 1972, directed by Arthur Hiller.

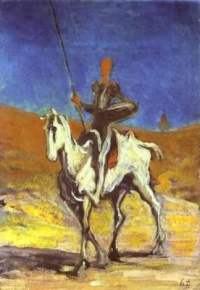

Don Quixote 's influence can be seen in the work of Smollett, Defoe, Fielding, and Sterne, as well as in the classic 19th-century novelists Scott, Dickens, Flaubert, Melville, and Dostoevsky, and in the works of James Joyce and Jorge Luis Borges. The theme of the novel also inspired the 19th-century French artists Honoré Daumier and Gustave Doré.

The Euro coins of €0.10, €0.20, and €0.50 made for Spain bear the portrait and signature of Cervantes.

Works

- El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha (1605): First volume of Don Quixote.

- Novelas ejemplares (1613): a collection of twelve short stories of varied types about the social, political, and historical problems of Cervantes' Spain:

- "La Gitanilla" ("The Gypsy Girl")

- "El Amante Liberal" ("The Generous Lover")

- "Rinconete y Cortadillo" ("Rinconete & Cortadillo")

- "La Española Inglesa" ("The English Spanish Lady")

- "El Licenciado Vidriera" ("The Lawyer of Glass")

- "La Fuerza de la Sangre" ("The Power of Blood")

- "El Celoso Extremeño" ("The Jealous Man From Extremadura")

- "La Ilustre Fregona" ("The Illustrious Kitchen-Maid")

- "Novela de las Dos Doncellas" ("The Novel of the Two Damsels")

- "Novela de la Señora Cornelia" ("The Novel of Lady Cornelia")

- "Novela del Casamiento Engañoso" ("The Novel of the Deceitful Marriage")

- "El Coloquio de los Perros" ("The Dialogue of the Dogs")

- Segunda Parte del Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha (1615): Second volume of Don Quixote.

- Los Trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (1617). Persiles, as it is commonly known, is the best evidence not only of the survival of Byzantine novel themes but also of the survival of forms and ideas of the Spanish novel of the second Renaissance. In this work, published after the author's death, Cervantes relates the ideal love and unbelievable vicissitudes of a couple, who, starting from the Arctic regions, arrive in Rome, where they find a happy ending to their complicated adventure.

- La Galatea, the pastoral romance, which Cervantes wrote in his youth, is an imitation of the Diana of Jorge de Montemayor and bears an even closer resemblance to Gil Polo's continuation of that romance. Next to Don Quixote and the Novelas Ejemplares, it is particularly worthy of attention, as it manifests in a striking way the poetic direction in which the genius of Cervantes moved even at an early period of life.

Don Quixote

Don Quixote (spelled "Quijote" in modern Spanish) is two separate volumes now nearly always published as one, that cover the adventures of Don Quixote, also known as the knight or man of La Mancha, a hero who carries his enthusiasm and self-deception to unintentional and comic ends. On one level, Don Quixote works as a satire of the romances of chivalry, which, though still popular in Cervantes' time, had become an object of ridicule among more demanding critics. The choice of a madman as hero also served a critical purpose, for it was "the impression of ill-being or 'in-sanity,' rather than a finding of dementia or psychosis in clinical terms, that defined the madman for Cervantes and his contemporaries." Indeed, the concept of madness was "associated with physical or moral displacement, as may be seen in the literal and figurative sense of the adjectives eccentric, extravagant, deviant, aberrant, etc." The novel also allows Cervantes to illuminate various aspects of human nature. Because the novel, particularly the first part, was written in individually published sections, the composition includes several incongruities. Cervantes himself however pointed out some of these errors in the preface to the second part; but he disdained to correct them, because he conceived that they had been too severely condemned by his critics. Cervantes felt a passion for the vivid painting of character. Don Quixote is noble-minded, an enthusiastic admirer of everything good and great, yet having all these fine qualities accidentally blended with a relative kind of madness. He is paired with a character of opposite qualities, Sancho Panza, a man of low self-esteem, who is a compound of grossness and simplicity.

Don Quixote is cited as the first classic model of the modern romance or novel, and it has served as the prototype of the comic novel. The humorous situations are mostly burlesque, and it includes satire. Don Quixote is one of the Encyclopædia Britannica's Great Books of the Western World, while the Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky called it "the ultimate and most sublime work of human thinking". It is in Don Quixote that Cervantes coined the popular phrase "the proof of the pudding is in the eating" (por la muestra se conoce el paño), which still sees heavy use in the shortened form of "the proof is in the pudding", and "who walks much and reads much, knows much and sees much" (quien anda mucho y lee mucho, sabe mucho y ve mucho).

Novelas Ejemplares (Exemplary Novels)

It would be scarcely possible to arrange the other works of Cervantes according to a critical judgment of their importance, for the merits of some consist in the admirable finish of the whole, while others exhibit the impress of genius in the invention, or some other individual feature. A distinguished place belongs to the Novelas ejemplares ("Moral or Instructive Tales"). They are unequal in merit as well as in character. Cervantes doubtless intended that they should be to Spanish nearly what the novellas of Boccaccio were to Italians. Some are mere anecdotes, some are romances in miniature, some are serious, some comic; all are written in a light, smooth, conversational style.

Four novelas are perhaps of less interest than the rest: El Amante Liberal, La Señora Cornelia, Las Dos Doncellas, and La Española Inglesa. The theme common to these is basically the traditional one of the Byzantine novel: pairs of lovers separated by lamentable and complicated happenings are finally reunited and find the happiness they have longed for. The heroines are all of most perfect beauty and of sublime morality; they and their lovers are capable of the highest sacrifices; and they exert their souls in the effort to elevate themselves to the ideal of moral and aristocratic distinction which illuminates their lives. In El Amante Liberal, to cite an example, the beautiful Leonisa and her lover Ricardo are carried off by Turkish pirates. Both fight against serious material and moral dangers. Ricardo conquers all obstacles, returns to his homeland with Leonisa, and is ready to renounce his passion and to hand Leonisa over to her former lover in an outburst of generosity; but Leonisa's preference naturally settles on Ricardo in the end.

Another group of "exemplary" novels is formed by La Fuerza de la Sangre, La Ilustre Fregona, La Gitanilla, and El Celoso Extremeño. The first three offer examples of love and adventure happily resolved, while the last unravels itself tragically. Its plot deals with the old Felipe Carrizales, who, after traveling widely and becoming rich in America, decides to marry, taking all the precautions necessary to forestall being deceived. He weds a very young girl - and isolates her from the world, by having her live in a house with no windows facing the street. But in spite of his defensive measures, a bold youth succeeds in penetrating the fortress of conjugal honour; and one day Carrizales surprises his wife in the arms of her seducer. Surprisingly enough he pardons the adulterers, recognizing that he is more to blame than they, and dies of sorrow over the grievous error he has committed. Cervantes here deviated from literary tradition, which demanded the death of the adulterers; but he transformed the punishment inspired, or rather required, by the social ideal of honour into a criticism of the responsibility of the individual. Rinconete y Cortadillo, El Casamiento Engañoso, El Licenciado Vidriera, and El Coloquio de los Perros, four works of art which are concerned more with the personalities of the characters who figure in them than with the subject matter, form the final group of these stories. The protagonists are, respectively, two young vagabonds, Rincón and Cortado, Lieutenant Campuzano, a student - Tomás Rodaja (who goes mad and believes himself to have been changed into a witty man of glass, offering Cervantes the opportunity to make profound observations) and finally two dogs, Cipión and Berganza, whose wandering existence serves to mirror the most varied aspects of Spanish life. El colloquio de los perros features even more sardonic observations on the Spanish society of the time.

Rinconete y Cortadillo is one of the most delightful of Cervantes' works. Its two young vagabonds come to Seville, attracted by the riches and disorder that the sixteenth-century commerce with the Americas had brought to that metropolis. There they come into contact with a brotherhood of thieves, the Thieves' Guild, led by the unforgettable Monipodio, whose house is the headquarters of the Sevillian underworld. Under the bright Andalusian sky, people and objects take form with the brilliance and subtle drama of a Velázquez. A distant and discreet irony endows the figures, insignificant in themselves, as they move within a ritual pomp that is in sharp contrast with their morally deflated lives. The solemn ritual of this band of ruffians is all the more comic for being presented in Cervantes' drily humorous style.

Los Trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (The Labors of Persiles and Sigismunda)

Cervantes finished the romance of Persiles and Sigismunda, shortly before his death. The idea of this romance was not new and Cervantes appears to imitate Heliodorus. The work is a romantic description of travels, both by sea and land. Real and fabulous geography and history are mixed together; and in the second half of the romance the scene is transferred to Spain and Italy.

Poetry

Some of his poems are found in La Galatea. He also wrote Dos Canciones à la Armada Invencible. His best work however is found in the sonnets, particularly Al Túmulo del Rey Felipe en Sevilla. Among his most important poems, Canto de Calíope, Epístola a Mateo Vázquez, and the Viaje del Parnaso (Journey to Parnassus - 1614) stand out. The latter is his most ambitious work in verse, an allegory which consists largely of reviews of contemporary poets. Compared to his ability as a novelist, Cervantes is often considered a mediocre poet, although he himself always harbored a hope that he would be recognized for having poetic gifts.

Viaje del Parnaso

The prose of the Galatea, which is in other respects so beautiful, is occasionally overloaded with epithet. Cervantes displays a totally different kind of poetic talent in the Viaje del Parnaso, a work which cannot properly be ranked in any particular class of literary composition, but which, next to Don Quixote, is considered by a few the most exquisite production of its author. Many critics, however, would argue with that, citing the Novelas Ejemplares and the Entemeses as the finest examples of his work next to Don Quixote.

Plays

Comparisons have diminished the reputation of his plays; but two of them (El Trato de Argel and La Numancia - 1582) made a big impact. The first of these, El Trato de Argel, is written in five acts. Based on his experiences as a captive of the Moors, the play deals with the life of Christian slaves in Algiers. The other play, Numancia, is a description of the siege of Numantia by the Romans. It is stuffed with horrors, and has been described as utterly devoid of the requisites of dramatic art. Cervantes's later production consists of 16 dramatic works, among which are eight full-length plays:

- El Gallardo Español (1615),

- Los Baños de Argel (1615),

- La Gran Sultana, Doña Catalina de Oviedo (1615),

- La Casa de los Celos (1615),

- El Laberinto de Amor (1615),

- La Entretenida, a cloak and dagger play, (1615)

- El Rufián Dichoso (1615),

- Pedro de Urdemalas (1615), a sensitive play about a picaro, who joins a group of Gypsies for love of a girl.

He also wrote eight short farces (entremeses) (1615):

- El Juez de los Divorcios,

- El Rufián Viudo Llamado Trampagos,

- La Elección de los Alcaldes de Daganzo,

- La Guarda Cuidadosa (The Vigilant Sentinel),

- El Vizcaíno Fingido,

- El Retablo de las Maravillas,

- La Cueva de Salamanca, and El Viejo Celoso (The Jealous Old Man).

These plays and entremeses made up Ocho Comedias y Ocho Entremeses Nuevos, Nunca Representados (Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes, Never Before Acted) which appeared in 1615. Cervantes' entremeses, whose dates and order of composition are not known, must not have been performed in their time. Faithful to the spirit of Lope de Rueda, Cervantes endowed them with novelistic elements, such as simplified plot, the type of description normally associated with the novel, and character development. The dialogue is sensitive and agile. Cervantes includes some of his dramas among those productions with which he was himself most satisfied, and he seems to have regarded them with self-complacency in proportion to their neglect by the public. This conduct has sometimes been attributed to a spirit of contradiction and sometimes to vanity. That the penetrating and profound Cervantes should have so mistaken the limits of his dramatic talent would not be sufficiently accounted for had he not unquestionably proved by his tragedy of Numantia how pardonable was the self-deception of which he could not divest himself.

Cervantes was entitled to consider himself endowed with a genius for dramatic poetry; but he could not preserve his independence in the conflict that he had to maintain with the Spanish public, who required certain conditions of dramatic composition; and when he sacrificed his independence, and submitted to rules imposed by others, his invention and language were reduced to the level of a poet of inferior talent. The intrigues, adventures, and surprises, which in that age characterized the Spanish drama (and which, we may assume, characterize all drama in every age) were ill suited to the genius of Cervantes. His natural style was too profound and precise to be reconciled to fantastical ideas, expressed in irregular verse; but he was Spanish enough to be gratified with dramas which as a poet he could not imitate; and he imagined himself capable of imitating them, because he would have shone in another species of dramatic composition had the public taste accommodated itself to his genius.

La Numancia

Cervantes invented, along with the subject of his piece, a peculiar style of tragic composition; and, in doing so, he did not pay much regard to the theory of Aristotle. His object was to produce a piece full of tragic situations, combined with the charm of the marvellous. In order to accomplish this goal, Cervantes relied heavily on allegory and on mythological elements. The tragedy is written in conformity with no rules, save those which the author prescribed for himself, for he felt no inclination to imitate the Greek forms. The play is divided into four acts, jornadas; and no chorus is introduced. The dialogue is sometimes in tercets, and sometimes in redondillas, and for the most part in octaves - without any regard to rule.