Don Quixote

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"Many an argument did he have with the curate of his village as to which had been the better knight, Palmerin of England or Amadis of Gaul." --Don Quixote (1605) by Miguel de Cervantes “In a place in La Mancha, the name of which I don't want to recall, there lived, not long ago, one of those gentlemen with a lance on the rack, an old shield, a worn-out horse, and a racing greyhound.”--incipit Don Quixote (1605) by Miguel de Cervantes "It is ironic that Cervantes's Don Quixote is described as the first novel (an extended work of prose fiction, written in "vulgar Latin", i.e. the people's language), the first modern novel (and the first psychological novel) due to its focus on the psychological evolution of a single character (an antihero) as well as the first postmodern novel (due of its use of self-reflexivity in the second volume)." --Sholem Stein "Don Quixote de la Mancha, says Sir Walter Scott, was the most determined as well as earliest bibliomaniac upon record, as among other slight indications of an infirm understanding, he exchanged fields and farms for folios and quartos of chivalry [...] Don Quixote acquired books not for themselves but for the stories of chivalrous knights whose deeds were the inspiration of those strange adventures which Cervantes invented as a whip for romantic pretensions."--The Anatomy of Bibliomania (1930) by Holbrook Jackson Sir Walter Scott, in his novel The Antiquary (1816), wrote: "The most determined, as well as earliest bibliomaniac upon record |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

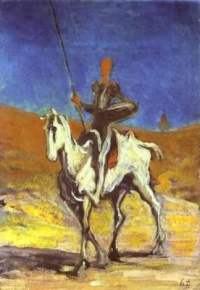

Don Quijote de la Mancha (1605) is novel by Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes. It is a parody of the mediaeval knight-errantry romance genre in general and Amadís de Gaula in particular.

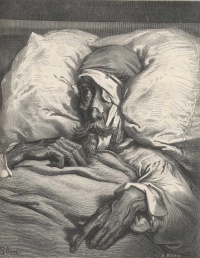

Published in two volumes a decade apart (in 1605 and 1615), its protagonist, Don Quixote has read himself into madness by reading too many chivalric romances. benencf

The novel also introduced Sancho Panza, the first use of the sidekick stock character.

Contents |

Themes

The novel's structure is in episodic form. It is written in the picaresco style of the late 16th century, and features reference other picaresque novels including Lazarillo de Tormes and The Golden Ass. The full title is indicative of the tale's object, as ingenioso (Spanish) means "quick with inventiveness" marking the transition of modern literature from Dramatic to thematic unity. The novel takes place over a long period of time, including many adventures all united by common themes of the nature of reality, reading, and dialogue in general.

Although farcical on the surface, the novel, especially in its second half, is more serious and philosophical about the theme of deception. Quixote has served as an important thematic source not only in literature but in much of art and music, inspiring works by Pablo Picasso and Richard Strauss. The contrasts between the tall, thin, fancy-struck, and idealistic Quixote and the fat, squat, world-weary Panza is a motif echoed ever since the book’s publication, and Don Quixote's imaginings are the butt of outrageous and cruel practical jokes in the novel. Even faithful and simple Sancho is unintentionally forced to deceive him at certain points. The novel is considered a satire of orthodoxy, veracity, and even nationalism. In going beyond mere storytelling to exploring the individualism of his characters, Cervantes helped move beyond the narrow literary conventions of the chivalric romance literature that he spoofed, which consists of straightforward retelling of a series of acts that redound to the knightly virtues of the hero.

From shepherds to tavern-owners and inn-keepers, the characterization in Don Quixote was groundbreaking. The character of Don Quixote became so well known in its time that the word quixotic was quickly adopted by many languages. Characters such as Sancho Panza and Don Quixote's steed, Rocinante, are emblems of Western literary culture. The phrase "tilting at windmills" to describe an act of attacking imaginary enemies derives from an iconic scene in the book.

It stands in a unique position between medieval chivalric romance and the modern novel. The former consist of disconnected stories featuring the same characters and settings with little exploration of the inner life of even the main character. The latter are usually focused on the psychological evolution of their characters. In Part I, Quixote imposes himself on his environment. By Part II, people know about him through "having read his adventures", and so, he needs to do less to maintain his image. By his deathbed, he has regained his sanity, and is once more "Alonso Quixano the Good".

When it was first published, Don Quixote was usually interpreted as a comic novel. After the French Revolution it was popular in part due to its central ethic that individuals can be right while society is quite wrong and seen as disenchanting—not comic at all. In the 19th century it was seen as a social commentary, but no one could easily tell "whose side Cervantes was on". Many critics came to view the work as a tragedy in which Don Quixote's innate idealism and nobility are viewed by the world as insane, and are defeated and rendered useless by common reality. By the 20th century the novel had come to occupy a canonical space as one of the foundations of modern literature.

False document

Cervantes created a fictional origin for the story in the character of the Moor historian, Cide Hamete Benengeli, whom he claims to have hired to translate the story from an Arabic manuscript he found in Toledo's bedraggled old quarter.

Madness by reading too much

The protagonist, Alonso Quixano, has read so many stories of chivalry that he descends into fantasy and becomes convinced he is a knight errant. Together with his companion Sancho Panza, the self-styled Don Quixote de la Mancha sets out in search of adventures. His "princesse lointaine" is Dulcinea del Toboso, an imaginary object of his courtly love crafted from a neighbouring farmgirl by the illusion-struck "knight" (her real name is Aldonza Lorenzo, and she is totally unaware of his feelings for her. In addition, she never actually appears in the novel).

This motif can also be found in Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina.

Influence

Published in two volumes a decade apart, Don Quixote is the most influential work of literature to emerge from the Spanish Golden Age and perhaps the entire Spanish literary canon. As a founding work of modern Western literature, it regularly appears at or near the top of lists of the greatest works of fiction ever published .

Influences upon literature and literary theory

The novel's landmark status in literary history has meant it has had a rich and varied influence over later writers, from Cervantes' own lifetime to the present-day. Some leading examples of Don Quixote's influence include:

- Cardenio, a lost play attributed to Cervantes's contemporary William Shakespeare. Itself the source of later plays, it is assumed to be based on one of the interpolated novels in the first part.

- Joseph Andrews (1742) by Henry Fielding notes on the title page that it is "written in Imitation of the Manner of Cervantes, Author of Don Quixote".

- The Female Quixote (1752), a novel by Charlotte Lennox in which a young woman's reading of romances leads her to misinterpret the world around her.

- Tristram Shandy (1759–67) by Laurence Sterne is rife with references, including Slawkenbergius' Tale and Parson Yorick's horse, Rocinante.

- The Spiritual Quixote (1773) by Richard Graves is a satire on Methodism.

- Don Chisciotti e Sanciu Panza (1785-1787) by Giovanni Meli (1740-1815) is a Sicilian parody of Don Quixote.

- The Pickwick Papers (1837), by Charles Dickens. The characters of Samuel Pickwick and Sam Weller, who roam London and get into all sorts of comic predicaments, are often compared to Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, although in this case, "Quixote" is the short, plump one, and "Sancho" is the tall, thin one.

- Madame Bovary (1856) by Flaubert was heavily influenced by Don Quixote.

- Prince Myshkin, the title character of Dostoyevsky's novel The Idiot (1869) was explicitly modelled on Don Quixote.

- "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote" (1939) by Jorge Luis Borges is an essay about a (fictional) 20th century writer who re-authors Don Quixote. "The text of Cervantes and that of Menard are verbally identical, but the second is almost infinitely richer." Borges' story is also well known as a central metaphor in John Barth's famous essay "The Literature of Exhaustion".

- Don Quixote appears as a character in Tennessee Williams's Camino Real (1953).

- Rocinante was the name Steinbeck gave his converted truck in his 1960 travelogue "Travels with Charley"

- Asterix in Spain (1969) by Goscinny and Uderzo. Asterix and Obelix encounter Don Quixote and Sancho Panza on a country road in Spain, with Quixote becoming enraged and charging off into the distance when the topic of windmills arises in conversation.

- A Confederacy of Dunces (1980) by John Kennedy Toole. The main character, Ignatius, is considered a modern-day Quixote.

- Monsignor Quixote (1982) by Graham Greene. Monsignor Quixote is said to be a descendant of Don Quixote.

- Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream (1986) also known as Don Quixote: a Novel by Kathy Acker, is a work of cyber-punk, post-feminist fiction that revisits the themes of the original text to highlight contemporary issues.

- The Moor's Last Sigh (1995) by Salman Rushdie, with its central themes of the world being remade and reinterpreted clearly draws enormous inspiration from Cervantes, with names and characters drawn from the earlier work.

- The novel plays an important part in Michel Foucault's book, The Order of Things. To Foucault, Quixote's confusion is an illustration of the transition to a new configuration of thought in the late sixteenth century. Quixote, by confusing semiology and hermeneutics, attempts to apply an anachronistic epistemological configuration to a new intellectual world, a new episteme, in which hermeneutics and semiology have been separated.

First novel ?

Miguel Cervantes's Don Quixote has been called "the first novel" by many literary scholars (or the first of the modern European novels). It was published in two parts. The first part was published in 1605 and the second in 1615. It might be viewed as a parody of Le Morte d'Arthur (and other examples of the chivalric romance), in which case the novel form would be the direct result of poking fun at a collection of heroic folk legends. This is fully in keeping with the spirit of the age of enlightenment which began from about this time and delighted in giving a satirical twist to the stories and ideas of the past. It's worth noting that this trend toward satirising previous writings was only made possible by the printing press. Without the invention of mass produced copies of a book it would not be possible to assume the reader will have seen the earlier work and will thus understand the references within the text.

Metafiction

Metafiction is primarily associated with postmodern literature but can be found at least as far back as Cervantes' Don Quixote.

Plot summary

Cervantes tells the story of the adventures of Don Quixote by way of a fictional Moorish chronicler named Cide Hamete Benengeli.

The protagonist of the book is Alonso Quixano (or Quijano), a retired country gentleman nearing 50 years of age, who lives in an unnamed section of La Mancha with his niece and a housekeeper. He has become obsessed with books of chivalry, and believes their every word to be true, despite the fact that many of the events in them are clearly impossible. Quixano eventually appears to other people to have lost his mind due to lack of sleep and food from dedicating all of his time to reading.

First quest

He decides to go out as a knight-errant in search of adventure. He dons an old suit of armor, renames himself "Don Quixote de la Mancha," and names his skinny horse "Rocinante". He designates a neighboring farm girl, Aldonza Lorenzo, as his lady love, renaming her Dulcinea del Toboso, while she knows nothing about this.

He sets out in the early morning and ends up at an inn, which he believes to be a castle. He asks the innkeeper, who he thinks to be the lord of the castle, to dub him a knight. He spends the night holding vigil over his armor, where he becomes involved in a fight with muleteers who try to remove his armor from the horse trough so that they can water their mules. The innkeeper then dubs him a knight, and sends him on his way. He frees a young boy who is tied to a tree by his master, because the boy had the audacity to ask his master for the wages the boy had earned but had not yet been paid (who is promptly beaten as soon as Quixote leaves). Don Quixote has a run-in with traders from Toledo, who "insult" the imaginary Dulcinea, one of whom severely beats Don Quixote and leaves him on the side of the road. Don Quixote is found and returned to his home by a neighboring peasant, Pedro Crespo.

Second quest

Don Quixote plots an escape. Meanwhile, his niece, the housekeeper, the parish curate, and the local barber secretly burn most of the books of chivalry, and seal up his library pretending that a magician has carried it off. Don Quixote approaches another neighbor, Sancho Panza, and asks him to be his squire, promising him governorship of an island. The uneducated Sancho agrees, and the pair sneak off in the early dawn. It is here that their series of famous adventures begin, starting with Don Quixote's attack on windmills that he believes to be ferocious giants.

In the course of their travels, the protagonists meet innkeepers, prostitutes, goatherds, soldiers, priests, escaped convicts, and scorned lovers. These encounters are magnified by Don Quixote’s imagination into chivalrous quests. Don Quixote’s tendency to intervene violently in matters which do not concern him, and his habit of not paying his debts, result in many privations, injuries, and humiliations (with Sancho often getting the worst of it). Finally, Don Quixote is persuaded to return to his home village. The author hints that there was a third quest, but says that records of it have been lost.

Part Two

Although the two parts are now normally published as a single work, Don Quixote, Part Two was a sequel published ten years after the original novel. While Part One was mostly farcical, the second half is more serious and philosophical about the theme of deception.

As Part Two begins, it is assumed that the literate classes of Spain have all read the first part of the history of Don Quixote and his squire. When they encounter the duo in person, the young scholar Samson Carrasco, an unnamed "duke and duchess," and others, seize the opportunity to amuse themselves by playing on Don Quixote's imaginings. The result is a series of cruel practical jokes that put Don Quixote's sense of chivalry and his devotion to Dulcinea through many humiliating tests.

Even Sancho deceives him at one point. Pressured into finding Dulcinea, Sancho brings back three dirty and ragged peasant girls, and tells Don Quixote that they are Dulcinea and her ladies-in-waiting. When Don Quixote only sees the peasant girls, Sancho pretends that their derelict appearance results from an enchantment. Sancho later gets his comeuppance for this when, as part of one of the duke and duchess's pranks, the two are led to believe that the only method to release Dulcinea from her spell is for Sancho to give himself three thousand lashes. Sancho naturally resists this course of action, leading to serious friction with his master. Under the duke's patronage, Sancho eventually gets an imaginary governorship, and unexpectedly proves to be wise and practical; though this, too, ends in humiliation.

Near the end, defeated and trampled, Don Quixote reluctantly begins to move back toward sanity. An inn is now just an inn, not a castle.

Conclusion

Upon returning to his village, Don Quixote announces his plan to retire to the countryside and live the pastoral existence of shepherd, although his housekeeper, who has a more realistic view of the hard life of a shepherd, urges him to stay home and tend to his own affairs. Soon after, he retires to his bed with a deathly illness, possibly brought on by melancholy over his defeats and humiliations. One day, he awakes from a dream having fully recovered his sanity. Sancho tries to restore his faith, but Alonso Quixano can only renounce his previous existence and apologize for the harm he has caused. He dictates his will, which includes a provision that his niece will be disinherited if she marries a man who reads books of chivalry. After Alonso Quixano dies, the author emphasizes that there are no more adventures to relate, and that any further books about Don Quixote would be spurious.

Translations

English translations

There are many translations of the book, and it has been adapted many times in shortened versions. Many derivative editions were also written at the time, as was the custom of envious or unscrupulous writers. Seven years after the Parte Primera appeared, Don Quixote had been translated into French, German, Italian, and English, with the first French translation of 'Part II' appearing in 1618, and the first English translation in 1620. One abridged adaptation, authored by Agustín Sánchez, runs slightly over 150 pages, cutting away about 750 pages.

Thomas Shelton's English translation of the First Part appeared in 1612 while Cervantes was still alive, although there is no evidence that Shelton had met the author. Although Shelton's version is cherished by some, according to John Ormsby and Samuel Putnam, it was far from satisfactory as a carrying over of Cervantes' text. Shelton's translation of the novel's Second Part appeared in 1620.

Near the end of the 17th century, John Phillips, a nephew of poet John Milton, published what Putnam considered the worst English translation. The translation, as literary critics claim, was not based on Cervantes' text but mostly upon a French work by Filleau de Saint-Martin and upon notes which Thomas Shelton had written.

Around 1700, a version by Pierre Antoine Motteux appeared. Motteux's translation enjoyed lasting popularity; it was reprinted as the Modern Library Series edition of the novel until recent times. Nonetheless, future translators would find much to fault in Motteux's version: Samuel Putnam criticized "the prevailing slapstick quality of this work, especially where Sancho Panza is involved, the obtrusion of the obscene where it is found in the original, and the slurring of difficulties through omissions or expanding upon the text". John Ormsby considered Motteux's version "worse than worthless", and denounced its "infusion of Cockney flippancy and facetiousness" into the original.

The proverb "The proof of the pudding is in the eating" is widely attributed to Cervantes. The Spanish word for pudding (Template:Lang), however, does not appear in the original text but premieres in the Motteux translation. In Smollett's translation of 1755 he notes that the original text reads literally "you will see when the eggs are fried", meaning "time will tell".

A translation by Captain John Stevens, which revised Thomas Shelton's version, also appeared in 1700, but its publication was overshadowed by the simultaneous release of Motteux's translation.

In 1742, the Charles Jervas translation appeared, posthumously. Through a printer's error, it came to be known, and is still known, as "the Jarvis translation". It was the most scholarly and accurate English translation of the novel up to that time, but future translator John Ormsby points out in his own introduction to the novel that the Jarvis translation has been criticized as being too stiff. Nevertheless, it became the most frequently reprinted translation of the novel until about 1885. Another 18th-century translation into English was that of Tobias Smollett, himself a novelist, first published in 1755. Like the Jarvis translation, it continues to be reprinted today.

A translation by Alexander James Duffield appeared in 1881 and another by Henry Edward Watts in 1888. Most modern translators take as their model the 1885 translation by John Ormsby.

An expurgated children's version, under the title The Story of Don Quixote, was published in 1922 (available on Project Gutenberg). It leaves out the risqué sections as well as chapters that young readers might consider dull, and embellishes a great deal on Cervantes' original text. The title page actually gives credit to the two editors as if they were the authors, and omits any mention of Cervantes.

The most widely read English-language translations of the mid-20th century are by Samuel Putnam (1949), J. M. Cohen (1950; Penguin Classics), and Walter Starkie (1957). The last English translation of the novel in the 20th century was by Burton Raffel, published in 1996. The 21st century has already seen five new translations of the novel into English. The first is by John D. Rutherford and the second by Edith Grossman. Reviewing the novel in the New York Times, Carlos Fuentes called Grossman's translation a "major literary achievement" and another called it the "most transparent and least impeded among more than a dozen English translations going back to the 17th century."

In 2005, the year of the novel's 400th anniversary, Tom Lathrop published a new English translation of the novel, based on a lifetime of specialized study of the novel and its history. The fourth translation of the 21st century was released in 2006 by former university librarian James H Montgomery, 26 years after he had begun it, in an attempt to "recreate the sense of the original as closely as possible, though not at the expense of Cervantes' literary style."

In 2011, another translation by Gerald J. Davis appeared. It is the latest and the fifth translation of the 21st century.

Dutch translations

- Den verstandigen vroomen ridder, Don Quichot de la Mancha (1657) Lambert van den Bos

- De vernuftige jonkheer Don Quichote van de Mancha (1854-59) by Christiaan Lodewijk Schuller tot Peursum

- A Flemish treatment of that text by René De Clercq (1930)

- Don Quichotte translated by Titia van der Tuuk

- De geestrijke ridder Don Quichot van de Mancha, a 1941-43 version by C.F.A. van Dam and J.W.F. Werumeus Buning, which, in a rich archaizing Dutch represented the knight as madder than he was in the original.

- The version of Barber van de Pol of 1997

See also

- Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda – author of a spurious sequel to Don Quixote, which in turn is referenced in the actual sequel

- List of best-selling books

- List of Don Quixote characters

- List of works influenced by Don Quixote – including a gallery of paintings and illustrations

- The 100 Best Books of All Time

- Tirant lo Blanc – one of the chivalric novels frequently referenced by Don Quixote

- Amadis de Gaula – one of the chivalric novels found in the library of Don Quixote

- António José da Silva – writer of Vida do Grande Dom Quixote de la Mancha e do Gordo Sancho Pança (1733)

- Belianis – one of the chivalric novels found in the library of Don Quixote

- coco – In the last chapter, the epitaph of Don Quijote identifies him as "el coco"

- Man of la Mancha, a musical play based on the novel.

Full text

- Don Quixote (full text of Ormsby translation, volume 1)

- Don Quixote (full text of Ormsby translation, volume 2)