Michelangelo

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 17:39, 17 December 2009 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 17:51, 17 December 2009 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) (→Sexuality) Next diff → |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| ==Sexuality== | ==Sexuality== | ||

| - | [[File:Michelangelo libyan.jpg|thumb|Drawing for ''The Libyan Sybil'', New York City, [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]]]] | ||

| - | [[File:LibyanSibyl SistineChapel.jpg|thumb|''The Libyan Sybil'', [[Sistine Chapel]], accomplished.]] | ||

| Fundamental to Michelangelo's art is his love of [[male beauty]], which attracted him both aesthetically and emotionally. In part, this was an expression of the Renaissance idealization of masculinity. But in Michelangelo's art there is clearly a sensual response to this aesthetic. | Fundamental to Michelangelo's art is his love of [[male beauty]], which attracted him both aesthetically and emotionally. In part, this was an expression of the Renaissance idealization of masculinity. But in Michelangelo's art there is clearly a sensual response to this aesthetic. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 15: | ||

| de' lor begli occhi, e del leggiadro aspetto | de' lor begli occhi, e del leggiadro aspetto | ||

| fan fede a quel ch'i' fu grazia nel letto, | fan fede a quel ch'i' fu grazia nel letto, | ||

| - | che abbracciava, e' n che l'anima vive.<ref>[http://www.oliari.com/storia/michelangelo.html "Michelangelo Buonarroti"] by Giovanni Dall'Orto Babilonia n. 85, January 1991, pp. 14–16 {{It icon}}</ref></poem> | + | che abbracciava, e' n che l'anima vive. |

| + | </poem> | ||

| |<poem>The flesh now earth, and here my bones, | |<poem>The flesh now earth, and here my bones, | ||

| Bereft of handsome eyes, and jaunty air, | Bereft of handsome eyes, and jaunty air, | ||

| Line 23: | Line 22: | ||

| Whom I embraced, in whom my soul now lives.</poem> | Whom I embraced, in whom my soul now lives.</poem> | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| - | According to others, they represent an emotionless and elegant re-imagining of Platonic dialogue, whereby erotic poetry was seen as an expression of refined sensibilities (Indeed, it must be remembered that professions of love in 16th century Italy were given a far wider application than now). Some young men were street wise and took advantage of the sculptor. Febbo di Poggio, in 1532, peddled his charms—in answer to Michelangelo's love poem he asks for money. Earlier, Gherardo Perini, in 1522, had stolen from him shamelessly. Michelangelo defended his privacy above all. When an employee of his friend Niccolò Quaratesi offered his son as apprentice suggesting that he would be good even in bed, Michelangelo refused indignantly, suggesting Quaratesi fire the man. | + | According to others, they represent an emotionless and elegant re-imagining of Platonic dialogue, whereby [[erotic poetry]] was seen as an expression of refined sensibilities (Indeed, it must be remembered that professions of love in 16th century Italy were given a far wider application than now). Some young men were street wise and took advantage of the sculptor. Febbo di Poggio, in 1532, peddled his charms—in answer to Michelangelo's love poem he asks for money. Earlier, Gherardo Perini, in 1522, had stolen from him shamelessly. Michelangelo defended his privacy above all. When an employee of his friend Niccolò Quaratesi offered his son as apprentice suggesting that he would be good even in bed, Michelangelo refused indignantly, suggesting Quaratesi fire the man. |

| The greatest written expression of his love was given to [[Tommaso dei Cavalieri]] (c. 1509–1587), who was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57. Cavalieri was open to the older man's affection: ''I swear to return your love. Never have I loved a man more than I love you, never have I wished for a friendship more than I wish for yours.'' Cavalieri remained devoted to Michelangelo until his death. | The greatest written expression of his love was given to [[Tommaso dei Cavalieri]] (c. 1509–1587), who was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57. Cavalieri was open to the older man's affection: ''I swear to return your love. Never have I loved a man more than I love you, never have I wished for a friendship more than I wish for yours.'' Cavalieri remained devoted to Michelangelo until his death. | ||

| - | Michelangelo dedicated to him over three hundred sonnets and [[wiktionary:madrigal|madrigals]], constituting the largest sequence of poems composed by him. Some modern commentators assert that the relationship was merely a Platonic affection, even suggesting that Michelangelo was seeking a surrogate son. However, their homoerotic nature was recognized in his own time, so that a decorous veil was drawn across them by his grand nephew, Michelangelo the Younger, who published an edition of the poetry in 1623 with the gender of pronouns changed. [[John Addington Symonds]], the early British homosexual activist, undid this change by translating the original sonnets into English and writing a two-volume biography, published in 1893. | + | Michelangelo dedicated to him over three hundred sonnets and [[madrigal|madrigals]], constituting the largest sequence of poems composed by him. Some modern commentators assert that the relationship was merely a Platonic affection, even suggesting that Michelangelo was seeking a surrogate son. However, their homoerotic nature was recognized in his own time, so that a decorous veil was drawn across them by his grand nephew, Michelangelo the Younger, who published an edition of the poetry in 1623 with the gender of pronouns changed. [[John Addington Symonds]], the early British homosexual activist, undid this change by translating the original sonnets into English and writing a two-volume biography, published in 1893. |

| The sonnets are the first large sequence of poems in any modern tongue addressed by one man to another, predating [[Shakespeare]]'s sonnets to his young friend by a good fifty years. | The sonnets are the first large sequence of poems in any modern tongue addressed by one man to another, predating [[Shakespeare]]'s sonnets to his young friend by a good fifty years. | ||

| Line 41: | Line 40: | ||

| Late in life he nurtured a great love for the poet and noble widow [[Vittoria Colonna]], whom he met in Rome in 1536 or 1538 and who was in her late forties at the time. They wrote sonnets for each other and were in regular contact until she died. | Late in life he nurtured a great love for the poet and noble widow [[Vittoria Colonna]], whom he met in Rome in 1536 or 1538 and who was in her late forties at the time. They wrote sonnets for each other and were in regular contact until she died. | ||

| - | It is impossible to know for certain whether Michelangelo had physical relationships ([[Ascanio Condivi|Condivi]] ascribed to him a "monk-like chastity"),<ref>Hughes, Anthony, "Michelangelo"., page 326. Phaidon, 1997.</ref> but through his poetry and visual art we may at least glimpse the arc of his imagination.<ref>Scigliano, Eric: [http://books.simonandschuster.ca/9780743254779 "Michelangelo's Mountain; The Quest for Perfection in the Marble Quarries of Carrara."], Simon and Schuster, 2005. Retrieved 27 January 2007</ref> | + | It is impossible to know for certain whether Michelangelo had physical relationships ([[Ascanio Condivi|Condivi]] ascribed to him a "monk-like chastity"), but through his poetry and visual art we may at least glimpse the arc of his imagination. |

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

Revision as of 17:51, 17 December 2009

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

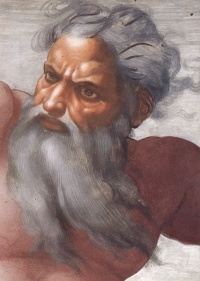

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (March 6, 1475 – February 18, 1564), commonly known as Michelangelo, was an Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, poet and engineer. Despite making few forays beyond the arts, his versatility in the disciplines he took up was of such a high order that he is often considered a contender for the title of the archetypal Renaissance man, along with his rival and fellow Italian Leonardo da Vinci. Indeed it was said that a true Renaissance man needed to have all these talents and also to have been a diplomat and that Michelangelo was the only person to have ever embodied these criteria.

Michelangelo's output in every field during his long life was prodigious; when the sheer volume of correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences that survive is also taken into account, he is the best-documented artist of the 16th century. Two of his best-known works, the Pietà and David, were sculpted before he turned thirty. Despite his low opinion of painting, Michelangelo also created two of the most influential works in fresco in the history of Western art: the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling and The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. As an architect, Michelangelo pioneered the Mannerist style at the Laurentian Library. At 74 he succeeded Antonio da Sangallo the Younger as the architect of Saint Peter's Basilica. Michelangelo transformed the plan, the western end being finished to Michelangelo's design, the dome being completed after his death with some modification.

In a demonstration of Michelangelo's unique standing, he was the first Western artist whose biography was published while he was alive. Two biographies were published of him during his lifetime; one of them, by Giorgio Vasari, proposed that he was the pinnacle of all artistic achievement since the beginning of the Renaissance, a viewpoint that continued to have currency in art history for centuries. In his lifetime he was also often called Il Divino ("the divine one"). One of the qualities most admired by his contemporaries was his terribilità, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur, and it was the attempts of subsequent artists to imitate Michelangelo's impassioned and highly personal style that resulted in Mannerism, the next major movement in Western art after the High Renaissance.

Sexuality

Fundamental to Michelangelo's art is his love of male beauty, which attracted him both aesthetically and emotionally. In part, this was an expression of the Renaissance idealization of masculinity. But in Michelangelo's art there is clearly a sensual response to this aesthetic.

The sculptor's expressions of love have been characterized as both Neoplatonic and openly homoerotic; recent scholarship seeks an interpretation which respects both readings, yet is wary of drawing absolute conclusions. One example of the conundrum is Cecchino dei Bracci, whose death, only a year after their meeting in 1543, inspired the writing of forty eight funeral epigrams, which by some accounts allude to a relationship that was not only romantic but physical as well:

<poem>La carne terra, e qui l'ossa mia, prive de' lor begli occhi, e del leggiadro aspetto fan fede a quel ch'i' fu grazia nel letto, che abbracciava, e' n che l'anima vive. </poem>

<poem>The flesh now earth, and here my bones, Bereft of handsome eyes, and jaunty air, Still loyal are to him I joyed in bed, Whom I embraced, in whom my soul now lives.</poem>

According to others, they represent an emotionless and elegant re-imagining of Platonic dialogue, whereby erotic poetry was seen as an expression of refined sensibilities (Indeed, it must be remembered that professions of love in 16th century Italy were given a far wider application than now). Some young men were street wise and took advantage of the sculptor. Febbo di Poggio, in 1532, peddled his charms—in answer to Michelangelo's love poem he asks for money. Earlier, Gherardo Perini, in 1522, had stolen from him shamelessly. Michelangelo defended his privacy above all. When an employee of his friend Niccolò Quaratesi offered his son as apprentice suggesting that he would be good even in bed, Michelangelo refused indignantly, suggesting Quaratesi fire the man.

The greatest written expression of his love was given to Tommaso dei Cavalieri (c. 1509–1587), who was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57. Cavalieri was open to the older man's affection: I swear to return your love. Never have I loved a man more than I love you, never have I wished for a friendship more than I wish for yours. Cavalieri remained devoted to Michelangelo until his death.

Michelangelo dedicated to him over three hundred sonnets and madrigals, constituting the largest sequence of poems composed by him. Some modern commentators assert that the relationship was merely a Platonic affection, even suggesting that Michelangelo was seeking a surrogate son. However, their homoerotic nature was recognized in his own time, so that a decorous veil was drawn across them by his grand nephew, Michelangelo the Younger, who published an edition of the poetry in 1623 with the gender of pronouns changed. John Addington Symonds, the early British homosexual activist, undid this change by translating the original sonnets into English and writing a two-volume biography, published in 1893.

The sonnets are the first large sequence of poems in any modern tongue addressed by one man to another, predating Shakespeare's sonnets to his young friend by a good fifty years.

<poem>

|

Late in life he nurtured a great love for the poet and noble widow Vittoria Colonna, whom he met in Rome in 1536 or 1538 and who was in her late forties at the time. They wrote sonnets for each other and were in regular contact until she died.

It is impossible to know for certain whether Michelangelo had physical relationships (Condivi ascribed to him a "monk-like chastity"), but through his poetry and visual art we may at least glimpse the arc of his imagination.