Giordano Bruno

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"Ambrogio on the one hundred twelfth thrust shall finally have driven home his business with his wife, but shall not impregnate her this time, but rather another, using the sperm into which the cooked leek that he has just eaten with millet and wine sauce shall have been converted."--The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast (1584) by Giordano Bruno "The fictitious image entails its own truth" --Giordano Bruno "the Cabala del Cavallo Pegaseo, contained a bitter attack upon the prevalent forms of Christian religion ; it especially attacked the doctrine of the all-sufficiency of faith, which, interpreted as it then was, might stand as the formula of mediaeval corruption and stagnation ; and it was upon this dialogue, almost solely, that the reputation Bruno long enjoyed — that of being an atheist — was based." --Giordano Bruno (James Lewis McIntyre) "In tristitia hilaris, in hilaritate tristis" --Giordano Bruno |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

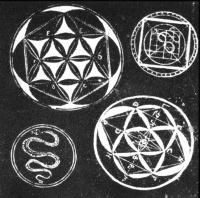

Giordano Bruno (1548 – 1600) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician, poet and astronomer. Bruno is known for his system of mnemonics based upon organized knowledge and as an early proponent of the idea of an infinite and homogeneous universe. Burned at the stake as a heretic for writing books like The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast (1584), Bruno is seen by some as the first martyr to the cause of freethought. All Bruno's works were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1603.

Contents |

Cosmology before Bruno

According to Aristotle and Plato, the universe was a finite sphere.(Although Aristotle explicitly claimed that Universe was infinite). Its ultimate limit was the primum mobile, whose diurnal rotation was conferred upon it by a transcendental God, not part of the universe, a motionless prime mover and first cause. The fixed stars were part of this celestial sphere, all at the same fixed distance from the immobile earth at the center of the sphere. Ptolemy had numbered these at 1,022, grouped into 48 constellations. The planets were each fixed to a transparent sphere.

In the first half of the 15th century Nicolaus Cusanus (not to be confused with Copernicus a century later) reissued the ideas formulated in Antiquity by Democritus and Lucretius and dropped the Aristotelean cosmos. He envisioned an infinite universe, whose center was everywhere and circumference nowhere, with countless rotating stars, the Earth being one of them, of equal importance. He also considered that neither were the rotational orbits circular, nor was the movement uniform.

In the second half of the 16th century, the theories of Copernicus (1473–1543) began diffusing through Europe. Copernicus conserved the idea of planets fixed to solid spheres, but considered the apparent motion of the stars to be an illusion caused by the rotation of the Earth on its axis; he also preserved the notion of an immobile center, but it was the Sun rather than the Earth. Copernicus also argued the Earth was a planet orbiting the Sun once every year. However he maintained the Ptolemaic hypothesis that the orbits of the planets were composed of perfect circles—deferents and epicycles—and that the stars were fixed on a stationary outer sphere.

Few astronomers of Bruno's time accepted Copernicus's heliocentric model. Among those who did were the Germans Michael Maestlin (1550–1631), Christoph Rothmann, Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), the Englishman Thomas Digges, author of A Perfit Description of the Caelestial Orbes, and the Italian Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). Curiously, Bruno's Nolan compatriot, Nicola Antonio Stigliola, born just two years before Bruno himself, believed in the Copernican model. The two, however, probably never met after their youth.

Retrospective views of Bruno

Some authors have characterized Bruno as a "martyr of science," suggesting parallels with the Galileo affair. They assert that, even though Bruno's theological beliefs were an important factor in his heresy trial, his Copernicanism and cosmological beliefs also played a significant role for the outcome. Others oppose such views, and claim this alleged connection to be exaggerated, or outright false.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "in 1600 there was no official Catholic position on the Copernican system, and it was certainly not a heresy. When [...] Bruno [...] was burned at the stake as a heretic, it had nothing to do with his writings in support of Copernican cosmology."

Similarly, the Catholic Encyclopedia (1908) asserts that "Bruno was not condemned for his defence of the Copernican system of astronomy, nor for his doctrine of the plurality of inhabited worlds, but for his theological errors, among which were the following: that Christ was not God but merely an unusually skilful magician, that the Holy Ghost is the soul of the world, that the Devil will be saved, etc."

However, the webpage of the Vatican Secret Archives discussing the document containing a summary of legal proceedings against him in Rome, suggests a different perspective: "In the same rooms where Giordano Bruno was questioned, for the same important reasons of the relationship between science and faith, at the dawning of the new astronomy and at the decline of Aristotle’s philosophy, sixteen years later, Cardinal Bellarmino, who then contested Bruno’s heretical theses, summoned Galileo Galilei, who also faced a famous inquisitorial trial, which, luckily for him, ended with a simple abjuration."

Following the 1870 Capture of Rome by the newly created Kingdom of Italy and the end of the Church's temporal power over the city, the erection of a monument to Bruno on the site of his execution became feasible. In 1885 an international committee was formed for that purpose, including Victor Hugo, Herbert Spencer, Ernest Renan, Ernst Haeckel, Henrik Ibsen and Ferdinand Gregorovius. The monument was sharply opposed by the clerical party, but was finally erected by the Rome Municipality and inaugurated in 1889.

A statue of a stretched human figure standing on its head designed by Alexander Polzin depicting Bruno's death at the stake was placed in Potsdamer Platz station in Berlin on March 2, 2008.

Imprisonment, trial and execution, 1593–1600

In Rome, Bruno's trial lasted seven years during which time he was imprisoned, lastly in the Tower of Nona. Some important documents about the trial are lost, but others have been preserved, among them a summary of the proceedings that was rediscovered in 1940. The numerous charges against Bruno, based on some of his books as well as on witness accounts, included blasphemy, immoral conduct, and heresy in matters of dogmatic theology, and involved some of the basic doctrines of his philosophy and cosmology. Luigi Firpo lists these charges made against Bruno by the Roman Inquisition:

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith and speaking against it and its ministers;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about the Trinity, divinity of Christ, and Incarnation;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith pertaining to Jesus as Christ;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith regarding the virginity of Mary, mother of Jesus;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about both Transubstantiation and Mass;

- claiming the existence of a plurality of worlds and their eternity;

- believing in metempsychosis and in the transmigration of the human soul into brutes;

- dealing in magics and divination.

Bruno continued his Venetian defensive strategy, which consisted in bowing to the Church's dogmatic teachings, while trying to preserve the basis of his philosophy. In particular, Bruno held firm to his belief in the plurality of worlds, although he was admonished to abandon it. His trial was overseen by the Inquisitor Cardinal Bellarmine, who demanded a full recantation, which Bruno eventually refused. On January 20, 1600, Pope Clement VIII declared Bruno a heretic and the Inquisition issued a sentence of death. According to the correspondence of Gaspar Schopp of Breslau, he is said to have made a threatening gesture towards his judges and to have replied: Maiori forsan cum timore sententiam in me fertis quam ego accipiam ("Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it").

He was turned over to the secular authorities. On February 17, 1600, in the Campo de' Fiori (a central Roman market square), with his "tongue imprisoned because of his wicked words", he was burned at the stake. His ashes were dumped into the Tiber river. All of Bruno's works were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1603.

Inquisition cardinals who judged Giordano Bruno were: Cardinal Bellarmino (Bellarmine), Cardinal Madruzzo (Madruzzi), Cardinal Camillo Borghese (later Pope Paul V), Domenico Cardinal Pinelli, Pompeio Cardinal Arrigoni, Cardinal Sfondrati, Pedro Cardinal De Deza Manuel, Cardinal Santorio (Archbishop of Santa Severina, Cardinal-Bishop of Palestrina).

Works

- De umbris idearum (Paris, 1582)

- Cantus Circaeus (1582) Latin text.

- De compendiosa architectura (1582)

- Candelaio (1582)

- Ars reminiscendi (1583)

- Explicatio triginta sigillorum (1583)

- Sigillus sigillorum (1583)

- La Cena de le Ceneri (Le Banquet des Cendres) (1584)

- De la causa, principio, et Uno (1584)

- De l'infinito universo et Mondi (1584)

- Spaccio de la Bestia Trionfante (L'expulsion de la bête triomphante) (London, 1584), allegory in which he attacks superstition

- Cabala del cavallo Pegaseo- Asino Cillenico(1585)

- De gl' heroici furori (1585)

- Figuratio Aristotelici Physici auditus (1585)

- Dialogi duo de Fabricii Mordentis Salernitani (1586)

- Idiota triumphans (1586)

- De somni interpretatione (1586)

- Animadversiones circa lampadem lullianam (1586)

- Lampas triginta statuarum (1586)

- Centum et viginti articuli de natura et mundo adversus peripateticos (1586)

- Delampade combinatoria Lulliana (1587)

- De progressu et lampade venatoria logicorum (1587)

- Oratio valedictoria (1588)

- Camoeracensis Acrotismus (1588)

- De specierum scrutinio (1588)

- Articuli centum et sexaginta adversus huius tempestatismathematicos atque Philosophos (1588)

- Oratio consolatoria (1589)

- De vinculis in genere (1591)

- De triplici minimo et mensura (1591)

- De monade numero et figura (Francfort, 1591)

- De innumerabilibus, immenso, et infigurabili (1591)

- De imaginum, signorum et idearum compositione (1591)

- Summa terminorum metaphisicorum (1595)

- Artificium perorandi (1612)

- Jordani Bruni Nolani opera latine conscripta, Dritter Band (1962) / curantibus F. Tocco et H. Vitelli

See also

- Satire of Divine providence in Giordano Bruno's 'The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast'

- Italian philosophy

- Giordano Bruno (Walter Pater)

- Giordano Bruno (James Lewis McIntyre)

- De Vinculis in Genere