Generale Riforma dell' Universo

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"THe Emperor Iustinian, that great Compiler of Statutes, and Books of Civil Law, some few daies since shewed a new Law to Apollo, to have his Majesties approbation of it: wherein men were strictly forbidden killing themselves. Apollo was so astonished at this Law, as fetching a deep sigh, he said; Is the good Government of mankind, Iustinian, fallen then into so great disorder, as men, that they may live no longer, do voluntarily kill themselves?"--"Generale Riforma dell' Universo" by Trajano Boccalini, Monmouth translation |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

"Generale Riforma dell' Universo dai sette Savii della Grecia e da altri Litterati" (Universal Reformation of Mankind by the Seven Wise Men of Greece, and by the Other Litterati) is a text by Trajano Boccalini.

The text is featured in Advertisements from Parnassus.

The text calls for a "general reformation of the world" proposed by the Seven Sages of Greece and Apollo.

It was translated into German by Christoph von Besold, in Dutch by Nicolaas Jarichides Wieringa and into English by Henry Carey, 2nd Earl of Monmouth.

Full text from

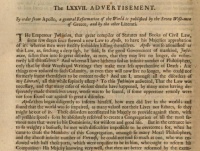

The LXXVII. ADVERTISEMENT.

By order from Apollo, a general Reformation of the world is published by the seven wise men of Greece, and by the other Litterati.

THe Emperor Iustinian, that great Compiler of Statutes, and Books of Civil Law, some few daies since shewed a new Law to Apollo, to have his Majesties approbation of it: wherein men were strictly forbidden killing themselves. Apollo was so astonished at this Law, as fetching a deep sigh, he said; Is the good Government of mankind, Iustinian, fallen then into so great disorder, as men, that they may live no longer, do voluntarily kill themselves? And whereas I have hitherto fed an infinite number of Philosophers, only that by their words and writings they may make men less apprehensive of death, are things now reduced to such calamity, as even they will now live no longer, who could not formerly frame themselves to be content to die? And am I amongst all the disorders of my Litterati all this while supinely asleep? To this Iustinian answered, That the Law was necessary, and that many cases of violent deaths having hapned, by many mens having desperately made themselves away, worse was to be feared, if some opportune remedy were not soon found out against so great a disorder.

Apollo then began diligently to inform himself, how men did live in the world; and found that the world was so impaired, as many valued not their lives nor Estates, so they might be out of it. These disorders necessitated his Majesty to provide against them with all possible speed; so as he absolutely resolved to create a Congregation of all the most famous men that were in his Dominions, for wisdom and good life. But in the entrance intoso weighty a business, he met with difficulties impossible to be overcome; for when he came to chuse the members of this Congregation, amongst so many moral Philosophers, and the almost infinite number of Vertuosi, he could not find so much as one, who was indowed with half those parts which were requisite to be in him, who ought to reform his companion: His Majesty knowing very well, that men are better reformed by the exemplary life of their reformers, then by any the best rules that can be given. In this great penury of fitting personages, Apollo gave the charge of the Universal Reformation to the seven wise men of Greece, who are of great repute in Parnassus, as those who are conceived by all men to have found out the receit of washing Blackmoors white. Which antiquity, though still in vain, hath so much laboured after. The Grecians were much rejoyc'd at this news, for the honor which Apollo had done their Nation; but the Latins were much grieved at it, thinking themselves thereby much injured. Wherefore Apollo very well knowing how much the ill satisfaction of those that are to be reformed, in their reformers, hinders the fruit which is to be hoped by reformation; and his Majesty being naturally given to appease his Subjects imbittered [Page 147]minds, more by giving them satisfaction, then by that Legislative power which men are not well pleased withall, because they are bound to obey it. That he might satisfie the Romans, who were much distasted, to the seven wise men of Greece, he added Marcus Cato, and Anneus Seneca: And in favour to the modern Italian Philosophers, he made Iacopo Mazzoni da Casena, Secretary of the Congregation, and honored him with a vote in their Consultations.

The 14 day of the last month, the seven wise men, with the aforesaid addition, accompanied by a Train of the choicest Vertuosi of this State, went to the Delfick Palace, the place appropriated for the reformation: And the Litterati were very well pleased to see the great number of Pedants, who with their little baskets in their hands, went gathering up the Sentences and Apothegmes, which fell from those wise men as they went along. The next day after the solemn entrance, the Assembly being met to give a beginning to the business, tis said Talete Milesio, the first wise man of Greece, spake thus;

The business (most wise Philosophers) about which were are all met in this place, is (as you all know) the greatest that can be treated on by human understanding: And though there be nothing harder then to set bones that have been long broken, wounds that are fistuled, and incurable cancars, yet difficulties which are able to affright others, ought not to make us despair of their cure; for the impossibility will increase our glory, and will keep us in the esteem we are in; and [...] do assure you that I have already found out the true Antidote against the poyson of all these present corruptions: I am sure we do all believe that nothing hath more corrupted the present age, then hidden hatreds, feigned love, impiety, the perfideousness of double-dealing men, cloaked under the specious mantle of simplicity, love to religion, and of charity; apply your selves to these evils Gentlemen, by making use of fire, razor, and lay corrosive Plasters to these wounds which I discover unto you; and all mankind, which by reason of their vices, which leads them the high-way to death, may be said to be given over by the Physitians, will soon be made whole and will become sincere and plain in their proceedings, true in what they say, and such in their sanctity of life, as they were in former times. The true and immediate cure then for these present evils, consists only in necessitating men to live with candor of mind, and purity of heart, which you will all confess with me, cannot be better effected, then by making that little window in mens brests, which, as being most requisite, his Majesty hath often promised to his most faithful Vertuosi: For when those who use such art in their modern proceedings, shall be forced to speak and act, having a window wherein one may see into their hearts, they will learn the excellent vertue of being, and not appearing to be; and will conform their deeds to their words, their tongus which are accustomed to dissembling, to sincerity of heart, and all men will banish lies and falshood, and the infirnal spirit of hypocrisie will abandon many who are now possest with so foul a fiend.

Talete's opinion did so please the whole Congregation, as being put to the vote, it was clearly carried for the affirmative; and Secretary Mazzoni was commanded to give Apollo a sudden account thereof, who perfectly approved the opinion, and gave command that that very day, the little window should be begun to be made in mans brest. But at the very instant [Page 148]hat the Surgeans took their instruments in hand to open mens brests, Virgil, Plato, Aristotle, Averoes, and other of the chief Litterati went to Apollo, and told him that he was not ignorant that the prime means whereby men do with much ease govern the world, was the reputation of those who did command; and that so pretious a jewel not being to be exposed to danger at any time by wise Princes, they beseeched his Majesty to consider in what esteem of holy life, and good demeanor, the reverend Philosophical Synod, and the honorable Colledge of the Vertuosi, were held by all the Litterati of Parnassus; that therefore they earnestly desired him (as it became him to do) to have a care of their honors, who by the fame of their goodness, increase the glory of Parnassus: And that if his Majesty should unexpectedly open every mans brest, the greater, and better sort of those Philosophers, who formerly were highly esteemed, ran evident hazard of being shamed; and that he might peradventure find fowlest faults in those whom he had formerly held to be immaculate. That therefore, before a business of such importance should be taken in hand, he would be pleased to afford his Vertuosi a competent time, to wash and cleanse their souls. Apollo was greatly pleased with the advice of so famous Poets and Philosophers, and by a publick Edict, prorogued the time of making the wind ows for eight daies; during which time, every one did so attend the cleansing and purging of their souls from all fallacies, from a hidden vice, from conceal'd hatred, and counterfeit love, as there was no more hony of roses, succory, cassia, scena, scamony, nor laxative syrups to be found in any Grocers or Apothecaries shop in all Parnassus: And the more curious did observe, that in the parts where the Platonicks, Peripateticks, and moral Philosophers did live, there was then such a stink, as if all the Privies of those Countries had been emptied: Whereas the quarters of Latin and Italian Poets, stunk only of Cabbadg-porrage. The time allotted for the general purging was already past, when the day before they were to begin making the windows, Hippocrates, Galen, Cornelius Celsus, and other the most skilfull Physitians of this State went to Apollo, and said, Is it then true, Sir, you that are the Lord of the Liberal Sciences, that this Microcosme must be deformed, which is so nobly and miraculously framed, as if any chief muscle, any principal vein be but touched, the human creature runs evident danger of being slain? and that so much mischief should be done only for the advantage of a few ignorant people? For not only the wiser sort of men, but even those of an indifferent capacity, who have converst but four daies with any Quacksalver, know how to penetrate even into the innermost bowels. This memorandum of the Physitians wrought so much with Apollo, as he changed his former resolution, and by Ausonius Gallus, bad the Philosophers of the Reformation, proceed in delivering their opinions.

Then Solon thus began; In my opinion, Gentlemen, that which hath put the present age into so great confusion, is the cruel hatred, and spitefull envy which in these daies is seen to reigne generally amongst men. All help then for these present evils, is to be hoped for from infusing charity, reciprocal affection, and that sanctified love of our neighbour, which is Gods chiefest commandment into mankind; we ought therefore to imploy all our skill in taking away the occasions of those hatreds, which in these daies reign in mens hearts; which if we be able to effect, men will do like beasts, who by the instinct of nature, love their own species; and [Page 149]will consequently drive away all hatred and rancor of mind. I have been long thinking, my friends, what the true springs head may be of all human hatred, and am still more established in my old opinion, that it proceeds from the disparity of means, from the hellish custom introduced amongst men of meum and tuum; the rise of all scandal; an abuse, which if it were introduced amongst the beasts of the earth, I assure my self, that even they would consume, and waste themselves with the self-same hatred and rancor wherewith we so much disquiet our selves: The not having any thing of propriety, and the equallity which they live in, is that which maintains that peace among them, which we so much envie in them. Men, as you all know, are likewise creatures, but rational; this world was created by Almighty God, only that mankind might live thereupon, as bruit beasts do; not that avaritious men should divide it amongst themselves, and should turn what was common, into that meum and tuum, which hath put us all into such confusion. So as it clearly appears, that the depravation of mens souls by avarice, ambition, and tyranny, hath occasioned the present inequality, and disproportionate division. And if it be true (as we all confess it is) that the world is nothing else but an Inheritance left to mankind by one only Father, and one only Mother, from whom we are all descended like brethren; what justice is it that every one should not have a share thereof equal with his companion? And what greater disproportion can there be imagined by those that love what is just, then that this world should be such, as that some possess more thereof then they can govern, and others have not so much as they could govern. But that which doth infinitely aggravate this disorder, is, that usually good and vertuous men are beggars; whereas wicked and ignorant people are wealthy. From the root of this inequality it then ariseth, that the rich are injurious to the poor, and that the poor envy the rich, For pride is proper to the rich, to beggars desperation. Hence it is that the rich mans oppressing the weak, appears to be natural; and the ill-will which poor men bear to the rich, is innate in them.

Now Gentlemen, that I have discovered the malady unto you, it is easie to apply the Medicine: I therefore think, that to reform this age, no better counsel can be taken, then to divide the world anew, and to allot an equal part thereof to every one. And that we may fall no more upon the like disorders, I advise, that for the future, all buying and selling be forbidden; so that parity of goods will be instituted; the Mother of publick Peace, which my self and other Law-makers, have formerly so much laboured for.

Solons opinion suffered a long debate; which though it was not only thought good, but necessary by Bante of Periandro, and by Pittaco, yet it was gainsaid by the rest; and Senecas opinion prevailed, who with very efficacious reasons made it appear, That if they should come to a new dividing of the world, the great disorder would necessarily follow, that too great a share would fall to Fools, and too little to gallant Men: And that the Plague, Famin, and Warr, were not Gods most severest scourges, with which God, when offended, did afflict mankind; but that his severest scourge for the punishment of man, and which out of his mercy, he made not use of, was to enrich rascals.

Solons opinion being laid aside, Chilon spake to this purpose; Which of you, my fellow-Philosophers, doth not know that the immoderate [Page 150]thirst that men now adaies have after gold, hath filled the world with all the mischiefs which we all see and feel? What wickedness, what impiety, how execrable soever, is it, which men do not willingly commit, if thereby they may accumulate riches? Conclude therefore unanimously with me, That no better way can be found out, whereby to extirpate all the vices wherewith our age is opprest, and to bring in that sort of life which doth best become men, then for ever to banish out of the world the two infamous Mettals, Gold and Silver; for so the occasion of our present disorders ceasing, the evils will likewise necessarily cease.

Chilons opinion was judged to have a very specious appearance; but when it came to the test, it would not endure the hammer: For it was said, that men took so much pains to get gold and silver, because they are the measure and counterpoise of all things; and that to make provision of all things necessary, it was requisite for men to have some mettals, or other thing of price, by which he might purchase what was fitting for him; and that if there were no such thing as gold or silver, men would make use of some other thing instead of them, which rising in value, would be as much coveted and sought after, as gold and silver now were; as was plainly seen in the Indies, where cockle-shels were made use of instead of money, and more vallued then either gold or silver. Cleobolus particularly being very hot in refuting this opinion, said, with much perturbation of mind; My masters, banish iron out of the world, for that is the mettal which hath put us into the present condition. Gold and silver serve for the use which is ordained by God, to be the measure of all things; whereas iron, which is produced by nature for the making of plow-shears, spades, and mattocks, and other instruments to cultivate the earth, is by the mallice and mischief of men, turned to the making of swords, and daggers, and other deadly instruments.

Though Cleobolus his opinion was judged to be very true, yet it was concluded by the whole Congregation, that it being impossible to expel iron, without grasping iron; and putting on Corslets, it would be a great piece of imprudency to multiply mischiefs, and to cure one wound with another. 'Twas therefore generally concluded, that the Ore of gold and silver should be still kept, but that the refiners of them should be wisht for the future to be sure to cleanse them well, and not to take them out of the fire, till they were certain they had taken from both the mettals, that vein of turpentine which they have in them, which is the reason why both gold and silver stick so close to the fingers even of good and honest men.

This being said, Pittacchus with extraordinary gravity, began thus; The World, Learned Philosophers, is fallen into that deplorable condition, which we so labour to amend, only because men in these daies have given over travailing by the beaten road-way of vertue, and take the bywaies of vice; by which, in this corrupted age, they obtain rewards only due to vertue. Things are brought to that woful state, as none can get entrance into the Palace of Dignity, Honor, or Reward (as formerly they had wont to do) by the Gate of Merit and vertuous endeavour, but like thieves, they climb the windows with ladders of tergeversation; and some there are, who by the force of gifts and favours, have opened the root, to get thereby into the house of Honour. If you will reform this our corrupted age, my opinion is, That you should do well to force men [Page 151]to walk by the way of vertue, and make severe Laws, that whosoever will take the laborsom journey which leads towards the obtaining of Supreme Honors and Dignities, must travail with the waggon of desert, and with the sure guide of vertue, and take away so many thwart by-waies, so many little paths, so many crooked lanes, found out by ambitious men, and modern Hypocrites, which multiplying faster in this our miserable age, then Locusts do in Africa, have filled the world with contagion. And truely what greater affront can there be put upon vertue and merit, then to see one of these companions arive at the highest preferments, when no man can guess what course he took to come by it? Which makes many think they have got it by the magick of hypocricy, whereby these Magicians do inchant the minds even of very wise Princes.

Pittacho's opinion was not only praised, but greatly admired by the whole Assembly, and certainly would have been approved of as very excellent, had not Periandro made those already almost resolved Philosophers alter their minds: For this Philosopher lively opposing the opinion of so great a Philosopher, said, Gentlemen, the disorder mentioned by Pittachus, is very true; but the thing which we ought chiefly to consider, is, for what reason Princes who are so quick-fighted, and interessed in their own State-affairs, do not bestow in these our daies their great places (as they were wont to do of old) on able and deserving men, by whose service they may receive advantage and reputation; but instead of them, make use of new fellows, raised out of the dirt and mire, without either worth or honor. You know, Gentlemen, that the opinion of those who say, that it is fatal to Princes to love carrion, and to imploy undeserving servant, in places of greatest trust, is so false, as for the least Interest of State, they neglect their brethren, and wax cruel even against their own children, so far are they from doting upon their servants in things wherein the welfare of their State lies. Princes do not act by chance, as many foolishly believe they do, nor suffer themselves to be guided in their proceedings by their passions, as we do; but whatsoever they do, is out of Interest; and those things which to privat men appear errors and negligence, are accurate politick Precepts. All that have written of State-affairs, freely confess that the best way to Govern Kingdoms well, is to confer places of highest honour and dignity upon men of great merit, and known worth and valor. This is a truth very well known to Princes; and though it be clearly seen that they do not observe it, he is a fool that believes they do it out of carelessness. I, who have long studied a point of so great weight, am verily perswaded, that ignorant and raw men, and men of no merit, are preferred by Princes, in conferring their chief Offices and honors, before learned and deserving men, not out of any fault in the Prince, but (I blush to say it) through default of the Vertuosi. I acknowledge that Princes stand in need of learned Officers, and men of experienced valor: But none of you will deny but that they likewise need men that are loyal and faithful. And it is evident, that if deserving men, and men of worth and valor were but as faithful as they are able, as gratefull as they are knowing, we should not complain of the present disorders, in seeing undeserving Dwarfs, become great Giants in four daies space, and should not bewail the wonder of seeing wild gourds in a short space overtop the best fruit-trees, nor to see ignorance seated in the Chair of Vertue, and folly in Vallors Tribunal. 'Tis common to all men to think [Page 152]much better of themselves then they deserve; but the Vertuosi do presume so very much upon their own good parts, as they rather pretend to add to the Princes reputation, by having any honors conferred upon them, then to receive credit themselves by his munificence: and I have known many so foolishly blown up, and inamored of their own worths, as they have thought it a greater happiness for a Prince to have an occasion of honouring such a one, then good luck for the other to meet with so liberal a Prince. So as these men acknowledging all favours confer'd upon them, to proceed from their own worth, prove so ungrateful to their Princes and benefactors in their greatest necessities, as causing themselves to be nauseated as very perfidious men, they are abhorred, and are causes of this present great disorder, why Princes, in such as they will prefer to great places, and high dignities, instead of merit, vertue, and known worth, seek for loyalty and trust, that they may meet with thankfulness when they stand in need of it; which they rather expect from those who pretending to no merit of their own, acknowledge all their good fortunes to proceed meerly from their Princes liberality.

Periandro having ended his discourse, Bias spake thus; All of you, most wise Philosophers, sufficiently know that the reason of the worlds being so depraved, is only because mankind hath so shamefully abandoned those holy Laws which God gave them to observe, when he bestowed the whole world upon them for their habitation: Nor did he place the French in France, the Spaniards in Spain, Dutch in Germany, and bound up the fowl fiend in hel, for any other reason, but for the advantage of that general peace which he desired might be observed throughout the whole world. But avarice and ambition (spurs which have alwaies egg'd on men to greatest wickedness) causing the French, Italians, Dutch, Grecians, and other Nations to pass into other mens Countries, have caused these evils which we (I wish it prove not in vain) endeavor to amend: And if it be true, as we all confess it is, that God hath done nothing in vain, and that there is much of mystery in all his operations; Wherefore think you, hath his Divine Majesty placed the inaccessable Perenian Mountains between the Spaniards and Italians; the rocky Alpes between the Italians and Germans; the dreadful English Channel between the French and English; why the Mediterranean Sea between Africa and Europe; why hath he made the infinite spacious Rivers of Euphrates, Indus, Ganges, Tigres, Danubius, Nilus, Rheine, and the rest; save only that people might be content to live in their own Countries, by reason of the difficulties of Fords and passages? And his Divine Majesty knowing very well that the harmony of universal peace would be out of tune, and that the world would be filled with uncurable diseases, if men should exceed the bounds which he had alloted them; that he might make the waies to such great disorders the more difficult, he added the multitude and variety of Languages, to the Mountains, Precipices, to the violent course of Rivers, and to the Seas immenceness: for otherwise, all men would speak the same Language, as all creatures of the same species, sing, bark, and bray, after one and the same manner. 'Tis then mans boldness in boaring through Mountains, and in passing over not only the largest and most rapid Rivers, but even in manifestly and rashly hazarding himself and all his substance in a little woodden Vessel, not fearing to cross the largest Seas therein; which caused the ancient Romans (not to mention the many other Nations [Page 153]who have run into the same rashness) to ruine other mens affairs, and discompose their own; not being satisfied with their Dominion over whole Italy. The true remedy then for so great disorder is, first to force every Nation to return home to their own Countreys; and to the end that the like mischiefs may not insue hereafter, I am of opinion, that all bridges built for the more commodious passing over rivers, be absolutely broken down; and the ways made for passing over the mountains may be quite spoil'd, and the mountains be made more inaccessable by mans industry, then they were at first made by nature; and I would have all navigation absolutely forbidden, upon severest penalty, not allowing so much as the least boats to pass in, over rivers. Bias his opinion was very attentively listened unto; and after being well examined by the best wits of the Assembly, it was found not to be good: for all those Philosophers knew, that the greatest enmities which are known to reign between Nation and Nation, are not natural (as many foolishly conceive them to be) but are occasioned by cunning Princes, who are great masters of the known proverb, Divide, & impera. And that that perfection of manners being found in all Nations joyned together, which was not to be had in any particular Province, men easily learn that exact wisdom by travelling through the world, which was peculiar to great Ulysses, who having travelled through many Countreys, had seen and observed the fashions of divers Nations; a benefit which was much furthered by the use of Navigation; which was very necessary for mankind, were it onely for that God (as well became the immencity of his power) having created this world of almost an incomprehensible greatness, having filled it with pretious things, and endowed every Province with somewhat of particular navigation, which is the rarest Invention that could ever have been thought on, or put in practice by humane wit, had brought it into so little a compass, as the Aromaticks of the Molucchi, though above fifteen thousand miles from Italy, do so abound in Italy, as if they grew there.

Thus ended Bias, when Cleobelus rising up, seeming with a low bow to crave leave to speak; said thus, I clearly perceive wise Gentlemen, that the reformation of the present Age, a business of it self very easie, becomes by the diversity and extravagancy of our Opinions, rather impossible then difficult. And to speak with the freedom which becomes this place, and the weight of the business we have in hand, it grieves my heart to find even amongst us that are here, that common defect of ambitious and slight wits, who getting up into publike pulpits, labor more to shew the rarity of their own wits, by their new and curious conceits, then to profit their Auditory by useful precepts and sound doctrines: for to raise man out of the foul mire and dirt whereinto he is fallen, what need we undertake that dangerous manifacture of making little windows in mens breasts, according to Thales his advice? and why should we undertake the laborous business of dividing the world into equal partitions, according to Solons proposition? and the course mentioned to be taken by Chilo, of banishing gold and silver from out of the world? or that of Pittacchus, of forcing men to walk in the way of merit and vertue? or lastly, that of Bias, that mountains should be raised higher, and made more difficult to pass over then nature hath made them, and that for the future the miracle of navigation should be extirpated, which [Page 154]shews to what pitch mans ingenuity can arrive, are they not sophistical fancies, and mear Chimera's? Our chiefest consideration ought to be, that the remedy to be applyed to the undoing evils, may be easie to be put in execution, that it may work its effect soon and secretly without any no [...]e, and that it may be chearfully received by those who are to be reformed: for by doing otherwise, we shall rather deform the World, then reform it. And certainly not without reason; for that Physician deserves to be blamed, who should ordain a medicine for his sick patient which is impossible to be used, and which would afflict him more then his disease. Therefore it is the requisite duty of Reformers, to provide themselves of a sure remedy, before they take notice of the wound: That Chyrurgion deserves to be punished, who first opens the sick mans vein, and then runs for things to close it up withal; it is not onely foolishness, but impiety, to defame men with publishing their vices, and to shew to the World that their maladies are grown to such a height, as it is not in the power of man to cure them. Therefore Tacitus, who always speaks to the purpose if he be rightly understood, doth in this particular advise men, Omittere potius pravallada, & adulta vitia, quam hoc assequi, ut palem fieret, quibus flagitiis impares essumus. Those who would fell an old Oak, are ill advised if they fall to cut down the top boughs: Wise men do, as I do now, lay the ax to the greatest root. I then affirm, That the reformation of the present world consists wholly in these few vvords, Premiar I buoni, e punire gli scelerati, in rewarding the good, and punishing the bad.

Here Cleobelus held his peace, whose Opinion Thales Mileseus, did with such violence oppose, as he shevved hovv dangerous a thing it is to offend such (though by telling truth) vvho have the repute to be good and vvise. For he vvith a fiery countenance broke forth into these vvords;

My self, and these Gentlemen, most vvise Cleobelus, since you have been pleased to reject our Opinions as sophistical, and meer Chimera s, did expect from your rare wisdom, that for cure of these present evils, you had brought some new and miraculous Bezoar fron the Indies, wheras you have propounded that for the easiest cure, which is the hardest and most impossible that could ever be fancied by the prime pretenders to high mysteries, Caius Plinius, and Albertus Magnus. There is not any one of us, my Cleobolus, that did not know, before you were pleased to put us in mind of it, that the reformation of the world, depends wholly upon rewarding such as are good and punishing the wicked. But give me leave to ask you, Who are those that in this our age are perfectly good, and who exactly ill? And I would know, Whether your eye can discern that which could never yet be found out by any man living, how to know true goodness from that which is counterfeit? do not you know▪ that modern hypocrites are arrived at that height of cunning, as in this our unhappy age, those are accounted to be cunningest in their wickedness, who seem to be most exactly good? and that such really perfect men who live in sincerity and singleness of soul, with an undisguised and unartificial goodness, without any thing of hypocrisie, are thought to be scandalous and silly? Every one by natural instinct loves those that are good, and hate those that are wicked, but Princes do it both out of instinct and interest. And when hypocrites, or other cunning [Page 155]cheaters are listened unto by great men, and good men supprest or undervalued, it is not by the Princes own election, but through the abuse of others. True vertue is known onely and rewarded by God, and vices discovered and punisht; for he onely penetrates into the depth of mens hearts, and we by means of the windovv by me propounded, might have penetrated thereinto, had not the enemy of mankind sovved tares in the field where I sovved the grain of good advice. But nevv lavvs, hovv good and vvholsome soever, have ever been and ever vvill be vvithstood by those vitious people vvho are thereby punished.

The Assembly vvere mightily pleased vvith the reasons alledged by Thales; and all of them turning their eyes upon Periandro, he thinking himself thereby desired to speak his opinion, began thus, The variety of opinions which I have heard, confirms me in my former Tenet▪ That four parts of five that are sick, perish because the Physicians know not their disease; who in this their error may be excused, because men are easily deceived in things wherein they can walk but by conjecture. But that we, who are judged by Apollo to be the salt of the earth, should not know the evil under which the present age labours, redounds much to our shame, since the malady which we ought to cure, lies not hidden in the veins but is so manifestly known to all men that it self crys aloud for help. And yet by all the reasons I have heard alledged, methinks you go about to mend the arm, when it is the breast that is fistula'd. But Gentlemen, since it is Apollo's pleasure, that we should do so, since our reputation stands upon it, and our charity to our so afflicted age requires it at our hands, let us, I beseech you, take from off our faces the mask of respect, which hath been hitherto worn by us all, and let us speak freely. The great disorder hath always reigned amongst men, which doth domineer so much at the present, and which God grant it may not still reign; that whilst powerful men by their detestible vices, and by their universal reformation, have disordered the world, men go about to re-order it by amending the faults of private men. But the falshood, avarice, pride and hypocrisie of private men (though I must confess them to be hainous evils) are not the vices which have so much depraved this our age; for fitting punishments being by the law provided for every fault, and foul action, mankind is so obedient to the laws, and so apprehensive of justice, as a few ministers thereof make millions of men tremble, and keeps them in, and men live in such quiet peace, as the rich cannot, without much danger to themselves oppress the poor, and every one may walk safely both by day and night with gold in their hand, not onely in the streets, but even in the high-ways: but the worlds most dangerous infirmities are then discovered, when publique peace is disturbed; and of this we must all of us confess, that the ambition, avarice and diabolical engagement, which the swords of some powerful Princes hath usurped over the States of those who are less powerful, is the true cause, and that which is so great a scandal to the present times: Tis this, Gentlemen, which hath filled the world with hatred and suspicion, and hath defiled it with so much blood, as men who were by God created with humane hearts, and civil inclinations, are become ravenous wilde beasts, tearing one another in pieces with all sort of inhumanity. For the ambition of these men hath changed publike peace into most cruel war, vertue into vice, the charity and love which we [Page 156]ought to bear to our neighbours, into such intestine hatred, as whereas all Lyons appear Lyons to a Lyon, the Scotch man appears unto the English, the Italian to the German, the French to the Spaniard, the German, Spaniard, French, and men of all other Nations to the Italian, not to be men, not brethren, as they are, but creatures of another species: So as justice being oppressed by the unexplicable ambition of potent men, mankind, which was born, brought up, and did live long under the Government of wholesome Laws, waxing now cruel to themselves, lives with the instinct of beasts, ready to oppress the weaker. Theft which is the chief of all faults, is so persecuted by the Laws, as the stealing of an egg is a capital fault, and yet powerful men are so blinded with the ambition of reigning, as to rob another man perfidiously of his whole state, is not thought to be an execrable mischief, as indeed it is, but an noble occupation, and onely fit for Kings; and Tacitus, the master of Policy, that he may win the good will of Princes, is not ashamed to say, In summa Fortuna id aequius quod vallidus, & sua retinere privatae domus, de Alienis certare Regiam laudem esse, li. 15. An. If it be true▪ which is confest to be so by all Politicians▪ that people are the Princes Apes, how can those who obey, live vertuously quiet, when their Commanders do so abound in vice? To bereave a powerful Prince of a Kingdom is a weighty business, which is not to be done by one man alone. To effect so foul an intent (observe what the thirst of Dominion can do in an ambitious mind) they muster together a multitude of men, who that they may not fear the shame of stealing their neighbours goods, of murthering men, and of firing Cities, change the name of base Thief into that of a gallant Souldier, and valliant commander; and that which aggravates this evil is, that even good Princes are forced to run upon the same rocks, to defend their own estates from the ravinousness of these Harpyes. For these to secure their own Estates, to regain what they have lost, and to revenge themselves of those that have injured them, possess themselves of their states: and being allured by gain, they betake themselves to the same shameful Trade, which they did so much abhor before. Which hath caused the art of bereaving other men of their Territories, become an highly esteemed science; and is the reason why humane wit, which was made to admire and contemplate the miracles of heaven, and wonders of the earth, is wholly turned to invent stratagems, to plot treasons; and hands, which were made to cultevate the earth which feeds us, into knowing how to handle Arms, that we may kill one another. This is that which hath brought our age to its last gasp; and the true way to remedy it is, for Princes who use such dealings▪ to amend themselves, and to be content with their own present Fortunes; for certainly it appears very strange to me, that there should be any King who cannot satisfie his ambition with the absolute command over twenty millions of men. Princes, as you all know, were ordained by God on earth, for the good of mankind; I therefore say it will not do well onely to bridle the ambition which Princes have of possessing themselves of other mens estates; but I think it necessary that the peculiar engagement which some men pretend their swords have over all estates, be cut up by the root; and I advise above all things, that the greatness of Principalities be limitted; it being impossible that too great Kingdoms should be governed with that exact care and justice [Page 157]which is requisite to the peoples good, and to which Princes are obliged. For there never was a Monarchy excessively over great, vvhich vvas not in a short time lost by the carelessness and negligence of those that were the Governors thereof.

Here Periandro ended; whom Solon thus opposed: The true cause of the present evils which you with much freedom have been pleased to speak of, vvas not omitted by us, out of ignorance (as you peradventure may believe) but out of prudence.

The disorders spoken of by you, that the weak were oppressed by those of greater power, began vvhen the World vvas first peopled. And you know, that the most skilful Physician, cannot restore sight to one that was born blind. I mention this, because it is much the same thing to cure an eye that is infirm, as to reform antiquated errors. For as the skilful Physician betakes himself the very first day that he sees an illaffected eye water, to his clouts and cauters, and is forced to leave his patient vvith a bleer eye; vvhen if the eye vvere quite blind, it vvere too late to seek for remedy; so reformers should oppose abuses vvith severe remedies, the very first hour that they commence. For when vice and corruption hath got deep rooting, it is wiselier done to tolerate the evil, then to go about to remedy it out of time, with danger to occasion worse inconveniences; it being more dangerous to cut of an old Wen, then it is misbecoming to let it stand. Moreover we are here to call to mind the disorders of private men, and to use modesty in so doing; but to be silent in what concerns Princes, and to bury their disorders, which a wise man must either touch very tenderly, or else say nothing of them; for they having no Superiors in this world, it belongs onely to God to reform them, he having given them the prerogative to command, us the glory to obey. And certainly not without much reason; for subjects ought to correct their Rulers defects onely by their own good and godly living. For the hearts of Princes being in the hands of God, when people deserve ill from his divine Majestie, he raiseth up Pharoahs against them, and on the contrary, makes Princes tender hearted, when people by their fidelity and obedience deserves Gods assistance.

What Solon had said, was much commended by all the hearers; and then Cato began thus:

Your opinions most wise Grecians are much to be admired; and by them you have infinitely verified the Tenet which all the Litterati have of you: for the vices, corruptions, and those ulcerated wounds, which the present age doth suffer under, could not be better nor more lively discovered and pointed out. Nor are your opinions, which are full of infinite wisdom, and humane knowledge, gain-said here; for that they were not excellently good; but for that the malady is so habituated in the veins, and is even so grounded in the bones, as that humane complexion is become so weak, as vital virtue gives place to the mightiness of vice, whereby we are made to know clearly, that the patient we have in hand is one sick of a consumption, who spits putrifaction, and whose hair fals from his head: The Physician hath a very hard part to play, Gentlemen, when the Patients maladies are many, and the one so far differing from the other, as cooling medicines, and such as are good for a hot liver, are nought for the stomach, and weaken it too much. And [Page 158]truly this is just our case; for the maladies which molest our present age, and wherewithal all other times have been affected, do for number equal the stars of heaven, or the sea-sands, and are more various, and further differing one from another, then are the flowers of the field. I therefore think this cure desperate, and that the patient is totally incapable of humane help: And my opinion is, That we must have recourse to prayers, and to other Divine helps, which in like cases are usually implored from God. And this is the true North-Star, which in the greatest difficulties leads men into the haven of perfection: for Pauci prudentia honesta ab deterioribus, utilia ab noxiis discernunt, plures aliorum eventis docentur. Tacit. lib. 4. Annal. And if we will approve, as we ought to do, of this consideration, we shall find, that when the world was formerly fallen into the like difficulties, it was no thought of man, but Gods care that did help it, who by sending universal deluges of water, razed mankind, full of abominable and incorrigible vice from off the world. And Gentlemen, when a man sees the walls of his house all gaping and runious, and the foundations so weakened, as in all appearance it is ready to fall, certainly it is more wisely done to pull down the house, and build it anew, then to spend his money, and waste his time in piecing and in patching it. Therefore since mans life is so foully depraved with vice, as it is past all humane power to restore it to its former health, I do with all my heart beseech the Divine Majestie, and counsel you to do the like, that he will again open the Cataracts of heaven, and send new deluges of water upon the earth, and so by pouring forth his wrath upon mankind, mend the incurable wounds thereof by the salve of death: but withal, that a new Ark may be made, wherein all boys of not above twelve years of age may be saved; and that all the female sex, of what soever age be so wholly consumed, as nothing but the unhappy memory thereof may remain. And I beseech the same Divine Majestie, that as he hath granted the singular benefit to Bees, Fishes, Beetles, and other annimals, to procreate without the feminine sex, that he will think men worthy the like favour. For Gentlemen, I have learnt for certain, that as long as there shall be any women in the world, men will be wicked.

It is not to be believed how much Cato's discourse displeased the whole Assembly, who did all of them so abhor the harsh conceit of a deluge, as casting themselves upon the ground, with their hands held up to heaven, they humbly beseeched Almighty God, that he would preserve the excellent femal sex, that he would keep mankind from any more Deluges, and that he should send them upon the earth onely to extirpate those discomposed and wilde wits, those untnuable and blood thirsty souls, those Hetorotrical and phantastick brains, who being of a depraved judgement, and out of an overweening opinion which they have of themselves, are in truth nothing but mad men, whose ambition was boundless, and pride without end; and that when mankind should through their misdemerits become unvvorthy of any mercy from his divine Majestie, he would be pleased to punish them with the scourges of Plague, Svvord and Famine, and that he vvould make use of his severest and of all others most cruel rod, as it is recorded by Seneca, of inriching mean men; but that he should keep from being so cruel, and causing such horrid calamity, as to deliver mankind unto the good vvill and [Page 159]pleasuree of those insolent vvicked Rulers, vvho being composed of nothing else but blind zeal, and diabolical folly, vvould pull the vvorld in pieces if they could compass and put in practice the beastial and odde Caprichios, vvhich they hourly hatch in their heads.

Cato's opinion had this unlucky end, when Seneca thus began:

Rough dealings is not so greatly requisite in point of Reformation, as it seems by many of your discourses, Gentlemen, to be; especially when disorders are grown to so great a height: The chief thing to be considered is to deal gently with them. They must be toucht with a light hand, like wounds which are subject to convulsions. It redounds much to the Physians shame, when the Patient dying with the potion in his body, every one knows the medicine hath done him more harm then his malady. It is a rash advice to go from one extreme to another, passing by the due medium: for mans nature is not capable of violent mutations; and if it be true, that the world hath been falling many thousand years into the present infirmities, he is onely not wise, but a very fool who thinks to restore it to its former health in a few days. And if a sick man, who formerly being fat, and after a long sickness is grovvn very lean, think in the first week of his convalessence to return to his former fatness by much eating, he must surely burst: but he will happily compass his desire, if he will eat moderately and have that patience which brings whatsoever knotty business to perfection. For quae longo tempore extenuantur Corpora, lentè reficere oportet. Hip. lib. 2. Aph. Moreover, in reformation, the conditions of those who do reform, and the quality of those that are to be reformed, ought to be exactly considered. We that are the reformers, are all of us Philosophers, learned men, if those that be to be reformed, be onely Stationers, Printers, such as sell Paper, Pens and Ink, and other such things appertaining to learning, we may very well correct their errors: but if we shall go about to mend the faults of other occupations we shall commit worse errors, and become more ridiculous then the Shoomaker who would judge of colours, and durst venture to censure Apelles his pictures. And upon this occasion I am forced to put you in mind of a fault which is usual amongst us the Litterati, who for four Cujus, which we have in our heads, pretend to know all things; and are not aware, that when we first swarve from what is treated on in our books, we run riot, and say a thousand things from the purpose. I say this, Gentlemen, because there is nothing which more obviates reformations, then to walk therein in the dark; which happens, when the Reformers are not perfectly well acquainted with the vices of those that are to be reformed. And the reason is apparent, for nothing makes men persevere more, and grow obstinate in their errors, then when they find that he that reforms, is not well informed of their defects who are to be reformed. And to prove this to be true, which of us is it, Gentleman, that knows what belong to the false hook of Notaries, to the prevarications of Advocates, the simony used by Judges, Proctors imbroylings, the abuses of Apothecaries, Taylors filtching, Butchers thieving, and of the cheating tricks of a thousand other Artificers? And yet all these excesses must be by us corrected. And if we shall go about to amend such disorders, which are so far from our profession, shall not we be thought as blind, as he who goes about to stop a hogshead, which being full of clefts, scatters [Page 160]out wine on every side? This is enough, Gentlemen, to let you know, that reformation is then likely to proceed well, when Marinors talk of winds, Souldiers of Wounds, Shepherds of sheep, and Herdsmen of Bullocks. It is manifest presumption in us to pretend to know all things, to believe that there are not three or four men of every Trade and Occupation, who fear God, and love their own reputation, is meer malice, and rash judgement. My opinion therefore is, That three or four of every Trade or Occupation, who are of known goodness and integrity, be sent for by us, and that every one reform his own Trade; for when Shoo-makers shall speak their opinion touching shoes and slippers, Taylors touching clothes, Chyrurgions concerning Searclothes, Cooks of Lard and Pickel'd meats, and every one shall correct his own Trade, we shall work a Reformation worthy of our selves, and of the present occasions.

Though Seneca's opinion was mightily praised by Petacchus and Chilo, who finding the other Philosophers to be of another opinion, entred their Protestation, that it was impossible to find out a better means for the reformation of mankind, then what had been mentioned by Seneca, yet did the rest of their companions abhor it more then they had done Cato's proposition; and moved with indignation, told him, That they much wondred, that by taking more reformers in into them, he would so far dishonour Apollo, who had thought them not onely sufficient, but excellently fit for that business. That it was not wisely advised to begin the general reformation by publishing their own weakness; for all resolutions which detract from the credit of the publishers, want that reputation which is the very soul of business, and that jurisdiction, which is more jealous then womens honor, should be handled so prodigally by such a one as he, who was the very prime Sage of Latin Writers; and that the very vvisest men did all agree, that twenty pound of blood taken from the very life-vain, was well imployed to gain but one ounce of jurisdiction; and that he is mad, who holding the svvord by the handle, gives it to his enemy to rescue it from him by the point.

The whole Assembly vvere mightily afflicted, vvhen by the refutation of Seneca's opinion, they found smal hopes of effecting the Reformation; for they relyed but little upon Mazzoni, vvho vvas but a novice, nor could they think that he could speak any thing to the purpose; vvhich though Mazzoni did by many signs perceive, yet no vvhit discouraged, he spoke thus;

It vvas not for any merit of mine, most vvise Philosophers, that I vvas admitted by Apollo into this reverend Congregation, but out of his Majesties special favour; and I very vvell knovv, that it better becomes me to use my ears then my tongue in so grave an Assembly as this, I being to learn and hold my peace. And certainly I should not dare to open my mouth upon any other occasion; but reformation being the business in hand, and I lately coming from vvhere nothing is spoken of but reformation and reformers, I desire, that every one may hold their peace, and that I alone may be heard to speak in a business vvhich I am so verst in, as I may boast my self to be the onely Euclide of this Mathematick. Give me leave, I beseech you, to say, That you, in relating your opinions, seem to me to be like those indiscrete Physicians, vvho lose time in consulting, and in disputing, vvithout having so much as [Page 161]seen the sick party, or heard his story for himself. We, Gentlemen, are to cure the present age of the foul infirmities vvherevvith vve see it is opprest. We have all laboured to find out the reasons of the maladies, and hovv to cure them, and none of us hath been so vvise as to visit the sick party. I therefore advise, Gentlemen, that vve send for the present age to come hither, that we interrogate it of its sickness, and that we may see the ill affected parts bare naked, and so the cure will prove easie, which you hold so desperate.

The whole Assembly was so pleased at this Mazzoni's motion, as the reformers immediately commanded the age to be sent for, which was presently brought in a chair to the Delphick Palace by the four Seasons of the year. He was a man full of years, but of so fresh and strong a complexion, as he seemed likely to live yet many ages; onely he was short breath'd, and his voyce vvas very weak: which the Philosophers wondring at; they asked him, Why his face being ruddy, which was sign that his natural heat was yet strong in him, and that his stomach was good: why, I say, he was so full of pain? and they told him, That a hundred year before, when his face was so yellow, as he s [...]med to have the Jaundice, he spoke freely notwithstanding, and seemed to be stronger then he was now. That they had sent for him to cure him of his infirmity, and bad him therefore freely speak his griefs.

The Age answered thus, Soon after I was born, Gentlemen, I fell into these maladies which I now labour under. My face is now so fresh and ruddy, because people have pe [...]er'd it, and coloured it with Lakes; My sickness resembles the ebbing and flowing of the sea, which always contains the same water, though it rise and fals; with this vicissitude notwithstanding, as when my looks are outwardly good, my malady (as at this present) is more grievous inwardly; and when my face looks ill, I am best within. For what my infirmities are, which do so torment me at the present, do but take off this gay Jacket, wherewith some good people have covered a rotten carcass, that notwithstanding breathes and view me naked, as I was made by Nature, and you will plainly see I am but a living carcass. All the Philosophers then hasted, and having stript the Age naked, they saw that the wretch pargeted with aparences four inches thick, all over his body. The Reformers caused ten razors to be forthwith brought unto them, and every one of them taking one, they fell all to scrape away the pargeting aforesaid; but they found them so far eaten into his very bones, as in all that huge Colossus, they could not find one ounce of good live flesh. At which they were much amazed, then put on the Ages Jacket again, and dismist him▪ and finding that the cure was altogether desperate, they assembled themselves close together, and forsaking the thought of all publike affairs they resolved to prepare for [...]r indempnity of their own reputations.

Mazzoni writ what the rest of the Reformers dictated, a Manifesto, wherein they witnessed to the world the great care Apollo ever had of his Litterati's vertuous living, and of the welfare of all mankind▪ and what pains the Reformers had taken in compiling the general Reformation. Then coming to particulars they set down the prizes o [...] ca [...]biges, s [...]rats, and pompions. And all the Assembly had already underwritten the reformation, when Thales put them in mind, that certa [...] H [...]glers, who sold Lupins, and black cherryes, vented such smal measures, as it was a shame not to take order therein.

[Page 162]The Assembly thankt Thales for his advertisement, and added to their reformation, that the measures should be made greater. Then the Palace Gates were thrown open, and the general Reformation was read in the place appointed for such purposes, to the people who were flockt in infinite numbers to the Market-place, and was so generally applauded by every one, as all Parnassus rung with shouts and vociferations of joy; for the meaner sort of people are pleased with every little thing; and men of judgement know that Vitia erunt, donec Homines, Tacit. Lib. 4. Hist. As long as there be men, there will be vices. That men live on earth, though not well, yet as little ill as they may; and that the height of human wisdom lay in being so discreet as to be content to leave the world as they found it.