Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

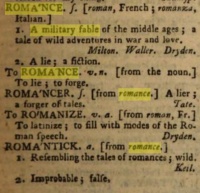

DR JOHNSON has defined Romance, in its primary sense, to be “a military fable of the middle ages; a tale of wild adventures in love and chivalry.” But although this definition expresses correctly the ordinary idea of the word, it is not sufficiently comprehensive to answer our present purpose. A composition may be a legitimate romance, yet neither refer to love nor chivalry — to war nor to the middle ages. The “wild adventures” are almost the only absolutely essential ingredient in Johnson's definition. We would be rather inclined to describe a Romance as “a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvellous and uncommon incidents;” being thus opposed to the kindred term Novel, which Johnson as “a smooth tale, generally of love;" but which we would rather define as “a fictitious narrative, differing from the Romance, because the events are accommodated to the ordinary train of human events, and the modern state of society.”.--"Essay on Romance" (c. 1813) by Walter Scott |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

"Essay on Romance" (c. 1813) is an essay on the nature of the novel by Walter Scott. Written as supplements to the EB, they were later collected in Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and the Drama.

It references Johnson's A Dictionary of the English Language.

Full text

AN ESSAY ON ROMANCE.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE SUPPLEMENT TO THE ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA.

ESSAY ON ROMANCE.

DR JOHNSON has defined Romance, in its primary sense, to be “a military fable of the middle ages; a tale of wild adventures in love and chivalry.” But although this definition expresses correctly the ordinary idea of the word, it is not sufficiently comprehensive to answer our present purpose. A composition may be a legitimate romance, yet neither refer to love nor chivalry — to war nor to the middle ages. The “wild adventures” are almost the only absolutely essential ingredient in Johnson's definition. We would be rather inclined to describe a Romance as “a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvellous and uncommon incidents;” being thus opposed to the kindred term Novel, which Johnson as “a smooth tale, generally of love;" but which we would rather define as “a fictitious narrative, differing from the Romance, because the events are accommodated to the ordinary train of human events, and the modern state of society.”

Assuming these definitions, it is evident, from the nature of the distinction adopted, that there may exist compositions which it is difficult to assign pre cisely or exclusively to the one class or the other and which, in fact, partake of the nature of both . But, generally speaking, the distinction will be found broad enough to answer all general and use 3 ful purposes. The word Romance, in its original meaning, was far from corresponding with the definition now assigned. On the contrary, it signified merely one or other of the popular dialects of Europe, founded ( as almost all these dialects were) upon the Roman tongue, that is, upon the Latin. The name of Romance was indiscriminately given to the Italian, to the Spanish, even in one remarkable instance at least) * to the English language. But it was espe

- This curious passage was detected by the industry of Ritson in Giraldus Cambrensis, “ Ab aqua illa optima, quæ Scottice

vocata est FROTH ; Brittanice, WAITE ; Romane vero Scotte Wattre. ” Here the various names assigned to the Frith of Forth are given in the Gaelic or Earse, the British or Welsh ; and the phrase Roman is applied to the ordinary language of England. But it would be difficult to show another instance of the English language being termed Roman or Romance. ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 157 cially applied to the compound language of France ; in which the Gothic dialect of the Franks, the Cel tic of the ancient Gauls, and the classical Latin, formed the ingredients. Thus Robert De Brunne : “ All is calde geste Inglis, That in this language spoken is Frankis speech is caled Romance, So sayis clerkis and men of France . ” At a period so early as 1150, it plainly appears that the Romance Language was distinguished from the Latin , and that translations were made from the one into the other ; for an ancient Romance on the subject of Alexander, quoted by Fauchet, says it was written by a learned clerk, “ Qui de Latin la trest, et en Roman la mit. ” 22 That is, “ who translated the tale from the Latin , and clothed it in the Romanece anguage." The most noted metrical tales or chronicles of the middle ages were usually composed in the Romance or French language, which, being spoken both at the Court of Paris and that of London, under the kings of the Norman race , became in a peculiar degree the speech of love and Chivalry. So much is this the case, that such metrical narratives as are writ ten in English always affect to refer to some French original, which usually, at least, if not in all in 158 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. stances, must be supposed to have had a real exist ence. Hence the frequent recurrence of the phrase, “ As in romance we read;" Or, Right as the romaunt us tells ;" and equivalent terms, well known to all who have at any time perused such compositions. Thus, very naturally, though undoubtedly by slow degrees, the very name of romaunt, or romance , came to be transferred from the language itself to that peculiar style of composition in which it was so much em ployed, and which so commonly referred to it. How early a transference so natural took place, we have no exact means of knowing ; but the best authority assures us, that the word was used in its modern and secondary sense so early as the reign of Edward III. Chaucer, unable to sleep during the night, informs us, that, in order to pass the time,, Upon my bed I sate upright, And bade one rechin me a boke, A ROMAUNCE, and it me took To read and drive the night away. ” The book described as a Romance contained, as we are informed , Fables That clerkis had , in old tyme, And other poets, put in rhyme. " 1 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 159 And the author tells us, a little lower, “ This book ne spake but of such things, Of Queens' lives and of Kings. ” The volume proves to be no other than Ovid's Me tamorphosis ; and Chaucer, by applying to that work the name of Romance, sufficiently establishes that the word was, in his time, correctly employed under the modern acceptation. Having thus accounted for the derivation of the word, our investigation divides itself into three prin cipal branches, though of unequal extent. In the FIRST of these we propose to inquire into the gene ral History and Origin of this peculiar species of composition, and particularly of Romances relating to European Chịvalry, which necessarily form the most interesting object of our inquiry. In the SECOND, we shall give some brief account of the History of the Romance of Chivalry in the differ ent states of Europe. THIRDLY, We propose to notice cursorily the various kinds of Romantic Composition by which the ancient Romances of Chivalry were followed and superseded, and with these notices to conclude the article. I. In the views taken by Hurd, Percy, and other older authorities, of the origin and history of roman 160 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. ✓ tic fiction , their attention seems to have been so ex clusively fixed upon the Romance of Chivalry alone, that they appear to have forgotten that, however in teresting and peculiar, it formed only one species ofa very numerous and extensive genus. The progress of Romance, in fact, keeps pace with that of society, which cannot long exist, even in the simplest state, without exhibiting some specimens of this attrac tive style of composition. It is not meant by this assertion, that in early ages such narratives were invented, as in modern times, in the character of mere fictions, devised to beguile the leisure of those who have time enough to read and attend to them . On the contrary, Romance and real history have the same common origin. It is the aim of the former to maintain as long as possible the mask of veracity ; and indeed the traditional memorials of all earlier ages partake in such a varied and doubt ful degree of the qualities essential to those opposite lines of composition, that they form a mixed class between them ; and may be termed either romantic histories, or historical romances, according to the proportion in which their truth is debased by fic tion, or their fiction mingled with truth . A moment's glance at the origin of society will satisfy the reader why this can hardly be otherwise. The father of an isolated family, destined one day | 2 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 161 to rise into a tribe, and in farther progress of time to expand into a nation , may, indeed , narrate to his descendants the circumstances which detach ed him from the society of his brethren, and drove him to form a solitary settlement in the wilderness, with no other deviation from truth , on the part of the narrator, than arises from the infidelity of me mory, or the exaggerations of vanity. But when the tale of the patriarch is related by his children , and again by his descendants of the third and fourth generation, the facts it contains are apt to assume a very different aspect. The vanity of the tribe augments the simple annals from one' cause — the X love of the marvellous, so natural to the human mind, contributes its means of sophistication from another — while, sometimes, from a third cause , the king and the priest find their interest in casting a holy and sacred gloom and mystery over the early period in which their power arose. And thus alter ed and sophisticated from so many different motives, the real adventures of the founder of the tribe bear as little proportion to the legend recited among his children, as the famous hut of Loretto bears to the highly ornamented church with which superstition has surrounded and enchased it. Thus the defini tion which we have given of Romance, as a fictitious narrative turning upon the marvellous or the su VOL . VI. L 162 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. pernatural, might, in a large sense, be said to em brace quicquid Græcia mendax Audet in historia, or, in fine, the mythological and fabulous history of all early nations. It is also important to remark, that poetry, or rather verse - rhythm at least of some sort or other, is originally selected as the best vehicle for these traditional histories. Its principal recommendation is probably the greater facility with which metrical narratives are retained in the memory — a point of the last consequence, until the art of writing is generally introduced ; since the construction of the verse itself forms an artificial association with the sense, the one of which seldom fails to recall the other to recollection . But the medium of verse, at first adopted merely to aid the memory, becomes soon valuable on account of its other qualities. The march or measure of the stanza is gratifying to the ear, and, like a natural strain of melody, can be restrained or accelerated, so as to correspond with the tone of feeling which the words convey ; while the recurrence of the necessary measuré rhythm, or rhyme, is perpetually gratifying the hearer by a sense of difficulty overcome. Verse being thus adopted as the vehicle of traditional history, there needs but the existence of a single man of genius, ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 163 in order to carry the composition a step higher in the scale of literature than that of which we are treating. In proportion to the skill which he attains in his art, the fancy and ingenuity of the artist him self are excited ; the simple narrative transmitted to him by ruder rhymers is increased in length ; is decorated with the graces of language, amplified in detail, and rendered interesting by description ; until the brief and barren original bears as little resemblance to the finished piece, as the Iliad of Homer to the evanescent traditions, out of which the blind bard wove his tale of Troy Divine. Hence the opinion expressed by the ingenious Percy, and assented to by Ritson himself. When about to pre sent to his readers an excellent analysis of the old Romance of Lybius Disconius, and making several remarks on the artificial management of the story , the Bishop observes, that “ if an Epic poem may be defined a fable related by a poet to excite admi ration and inspire virtue, by representing the action of some one hero favoured by Heaven , who executes a great design in spite of all the obstacles that oppose him, I know not why we should withhold the name of Epic Poem from the piece which I am X about to analyse." Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, III. xxvii . The Pre .. late is citing a discourse on Epic Poetry, prefixed to Telemachus. 164 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. Coestay stry X toweld two , though ,in ena wash Yet although this levelling proposition has been laid down by Percy, and assented to by Ritson ( writers who have few opinions in common ), and al though, upon so general a view of the subject, the Iliad, or even the Odyssey, of Homer might be degraded into the class of Romances, as Le Beau Deconnu is elevated into that of epic poems, there lies in ordinary speech, and in common sense, as wide a distinction between these two classes of com position, as there is betwixt the rude mystery or morality of the middle ages, and the regular drama by which these were succeeded. Where the art and the ornaments of the poet chiefly attract our atten tion — where each part of the narrative bears a due proportion to the others, and the whole draws gra dually towards a final and satisfactory conclusion where the characters are sketched with force, and sustained with precision — where the narrative is enlivened and adorned with so much, and no more, of poetical ornament and description, as may adorn, without impeding its progress — where this art and taste are displayed, supported, at the same time, by a sufficient tone of genius, and art of composition, the work produced must be termed an Epic Poem , and the author may claim his seat upon the high and honoured throne occupied by Homer, Virgil, and Milton . On the other hand, when a story lan ESSAY ON ROMANCE . 165 guishes in tedious and minute details, and relies for the interest which it proposes to excite, rather upon the wild excursions of an unbridled fancy, than upon the skill of the poet - when the super natural and the extraordinary are relied upon ex clusively as the supports of the interest, the author, though his production may be distinguished by occasional flashes of genius ,and though it may be interesting to the historian, as containing some mi nute fragments of real events, and still more so to the antiquary, from the light which it throws upon ancient manners, is still no more than a humble romancer, and his works must rank amongst those rude ornaments of a dark age, which are at present the subject of our consideration. Betwixt the extremes of the two classes of composition, there must, no doubt, exist many works, which partake in some degree of the character of both ; and after having assigned most of them each to their proper class, according as they are distinguished by regu larity of composition and poetical talent, or, on the contrary, by extravagance of imagination, and irre gularity of detail, there may still remain some, in which these properties are so equally balanced , that it may be difficult to say to which class they belong. But although this may be the case in a very few instances, our taste and habits readily acknowledge 166 ESSAY ON ROMANCE ., So,differ Amerients as complete and absolute a difference betwixt the Epopeia and Romance, as can exist betwixt two distinct species of the same generic class. We have said of Romance, that it first appears in the form of metrical history, professes to be a narrative of real facts, and is, indeed, nearly allied to such history as an early state of society affords ; which is always exaggerated by the prejudices and partialities of the tribe to which it belongs, as well as deeply marked by their idolatry and superstition. These it becomes the trade of the romancers still more to exaggerate, until the thread of truth can scarce be discerned in the web of fable which in volves it ; and we are compelled to renounce all hope of deriving serious or authentic information from the materials upon which the compounders of fic tion have been so long at work , from one generation to another, that they have at length obliterated the very shadow of reality or even probability. The view we have given of the origin of Ro mance will be found to agree with the facts which the researches of so many active investigatorsof this curious subject have been able to ascertain . It is found, for example, and we will produce instances in viewing the progress of Romance in particular countries, that the earliest productions of this sort, known to exist, are short narrations or ballads, ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 167 Highlands which were probably sung on solemn or festival oc casions, recording the deeds and praises of some famed champion of the tribe and country, or per haps the history of some remarkable victory or sig nal defeat, calculated to interest the audience by the associations which the song awakens. These poems, of which very few can now be supposed to exist, are not without flashes of genius, but brief, rude, and often obscure, from real antiquity or af fected sublimity of diction . The song on the battle of Brunanburgh, preserved in the Saxon Chronicle, is a genuine and curious example of this aborigiual style of poetry. Even at this early period,* there may be obser ved a distinction betwixt what may be called the Temporal and Spiritual Romances ; the first desti ned to the celebration of worldly glory,—the second to recording the deaths of martyrs and the miracles of saints ; both which themes unquestionably met with an almost equally favourable reception from their hearers. But although most nations possess, in their early species of literature, specimens of both kinds of Romance, the proportion of each , as was naturally to have been expected, differs according

- The religious Romances of Barlaam and Jehosaphat were

composed by John of Damascus in the eighth century. 168 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. as the genius of the people amongst whom they oc cur leaned towards devotion or military enterprise. Thus, of the Saxon specimens of poetry, which ma nuscripts still afford us, a very large proportion is devotional, amongst which are several examples of the Spiritual Romance, but very few indeed of those respecting warfare or chivalry. On the other \ hand, the Norman language, though rich in ex amples of both kinds of Romancet, is particularly abundant in that which relates to battle and war like adventure. The Christian Saxons had become comparatively pacific, while the Normans were cer tainly accounted themost martial people in Europe. However different the Spiritual Romance may be from the temporal in scope and tendency, the nature of the two compositions did not otherwise greatly differ. The structure of verse and style of composition was the same ; and the induction , even when the most serious subject was undertaken , exactly resembled that with which minstrels intro duced their idle tales, and often contained allusions to them . Warton quotes a poem on the Passions, which begins, I hereth one lutele tale, that Ich eu wille telle, As wi vyndeth hit invrite in the godspelle, Nuz hit nouht of Carlemeyne ne of the Duzpere, Ac of Criste's thruurynge, &c . ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 169 The Temporal Romances, on the other hand, often commenced by such invocations of the Deity, as would only have been in place when a much more solemn subject was to be agitated. The ex ordium of the Romance of Ferumbras may serve as an example of a custom almost universal : God in glorye of mightis moost That all things made in sapience, By virtue of Word and Holy Gooste, Giving to men great excellence, & c . The distresses and dangers which the knight en dured for the sake of obtaining earthly fame and his mistress's favour, the saint or martyr was expo sed to for the purpose of securing his rank in hea ven, and the favour of some beloved and peculiar patron saint. If the earthly champion is in peril from monsters, dragons, and enchantments, the spi ritual hero is represented as liable to the constant assaults of the whole invisible world, headed by the ancient dragon himself. If the knight is succoured at need by some favouring fairy or protecting ge nius, the saint is under the protection not only of the whole heavenly host, but of some one divine patron or patroness who is his especial auxiliary. Lastly, the conclusion of the Romance, which usu ally assigns to the champion a fair realm , an abun dant succession , and a train of happy years, consigus 170 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. EN to the martyr his fane and altar upon earth, and in heaven his seat among saints and angels, and his share in a blessed eternity. It remains but to say , that the style and language of these two classes do not greatly differ, and that the composers of both employ the same structure of rhythm and of lan guage, and draw their ideas and their incidents from similar sources ; so that, having noticed the exist ence of the Spiritual Romance, it is unnecessary for the present to prosecute this subject farther. Another early and natural division of these works of fiction seems to have arranged them into Serious and Comical. The former were by far the most numerous, and examples of the latter are in most countries comparatively rare . Such a class, however, existed, as proper Romances, even if we hold the Comic Romance distinct from the Contes and Fa bliaux of the French , and from such jocular Eng lish narratives as the Wife Lapt in Morils Skin , The Friar and the Boy , and similar humorous tales : of which the reader will find many examples in Ritson's Ancient English Poetry, and in other collections. The scene of these gestes being laid in low, or at least in ordinary life, they approach in their nature more nearly to the class of novels, and may perhaps be considered as the carliest spe cimens of that kind of composition. But the pro XХ 2 ESSAY ON ROMANCE . 171 per Comie Romance was that in which the high , terms and knightly adventures of chivalry were a burlesqued, by ascribing them to clowns, or others , of a low and mean degree. Such compositions form- / ed, as it were, a parody on the Serious Romance, to which they bore the same proportion as the anti masque, studiously filled with grotesque, absurd, and extravagant characters, “ entering," as thestage direction usually informs us, “ to a confused mu sic, ” bore to the masque itself, where all was dig nified , noble, stately, and harmonious. An excellent example of the Comic Romance is the Tournament of Tottenham , printed in Percy's Reliques, in which a number of clowns are intro duced practising one of those warlike games, which were the exclusive prerogative of the warlike and noble. They are represented making vows to the swan, the peacock, and the ladies ; riding a tilt on their clumsy cart horses, and encountering each other with plough -shares, and flails ; while their defensive armour consisted of great wooden bowls and troughs, by way of helmets and cuirasses. The learned editor seems to have thought this sin gular composition was, like Don Quixote, with which he compares it, a premeditated effort of sa tire, written to expose the grave and fantasticman ners of the Serious Romance. This is considering 172 ESSAY ON ROMANCE . the matter too deeply, and ascribing to the author of the Tournament of Tottenham , a more critical purpose than he was probably capable of concei ving. It is more natural to suppose that his only ambition was to raise a laugh, by ascribing to the vulgar the manners and exercises of the noble and valiant ; as in the well- known farce of High Life Below Stairs, the ridicule is not directed against the manners described, but against the menials who affect those that are only befitting their su periors. The Hunting of the Hare, published in the collection formed by the late industrious and ac curate Mr Weber, is a comic Romance of the same order. A yeoman informs the inhabitants of a country hamlet that he has found a hare sitting, and inquires if there is any gentleman near who keeps greyhounds, for the purpose of coursing her. The villain to whom he communicates this infor mation replies, there is no need of sending for a gentleman's assistance, and proceeds to enumerate the catalogue of ban -dogs, which are the property of himself and the other clowns of the village : “ Hob Andrew Y thynke on now, He has a dogge wyll take a sow, And bryng hur to the cowtte ; Ther is no thyng he wyll forsake, Ye schall se hym this hare take, And gnaw ate hur throwtte. ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 173 “ Parkyn the potter, hase iij that wyll not fayll ; Short schonkes and neuer a tayll : No kalfe so greyt, as Y wene, So has Dykon and Jac Gryme, So has yonge Raynall and Sym, And all the schall hom sene. " When the chase is assembled, the yeoman puts up the hare, who with little difficulty makes her escape from the mongrel mastiffs, and breaks a ring which had been formed by the peasants, armed with their great clubs and bats. Great is the terror of the individual over whom she ran in her retreat, and who expected fully that she would have torn his throat out. The inexperienced curs and mastiffs, instead of pursuing the game, commence a battle royal amongst themselves ,—their masters take part in the fray, and beat each other soundly. In short, the hunting of the hare, scarce less doleful than that of Cheviot, concludes like the latter, with the women of the village coming to carry off the wound ed and slain . It can hardly be supposed the satire is directed against the sport of hunting itself ; since the whole ridicule arises out of the want of the necessary knowledge of its rules, incident to the ignorance and inexperience of the clowns, who undertook to practise an art peculiar to gentlemen. The ancient poetry of Scotland furnishes several 174 ESSAY ON ROMANCE . examples of this ludicrous style of romantic com position ; as the Tournament at the Drum , and the Justing of Watson and Barbour, by Sir David Lindsay. It is probable that these mock encoun ters were sometimes acted in earnest ; at least King James I. is accused of witnessing such practical jests ; “ sometimes presenting David Droman and Archie Armstrong, the King's fool, on the back of other fools, to tilt at one another till they fell to gether by the ears." -- (Sir Antony Weldon's Court of King James.) In hastily noticing the various divisions of the Romance, we have in some degree delayed our pro mised account of its rise and progress ; an inquiry which we mean chiefly to confine to the Romance of the middle ages. It is indeed true that this species of composition is common to almost all na tions, and that even if we deem the Iliad and Odys sey compositions too dignified by the strain of poe try in which they are composed to bear the name of Metrical Romances ; yet we have the Pastoral Romance of Daphnis and Chloe, and the Historical Romance of Theagenes and Chariclea , which are sufficiently accurate specimens of that style of com position . The Milesian fables and the Romances of Antonius Diogenes, described by Photius, could they be recovered, would also be found to belong to ESSAY ON ROMANCE . 175 the same class. It is impossible to avoid noticing that the Sybarites, whose luxurious habits seem to have been intellectual, as well as sensual, were pecu liarly addicted to the perusal of the Milesian fables ; from which we may conclude that the narratives were not of that severe kind which inspired high thoughts and martial virtues. But there would be little advantage derived from extending our re searches into the ages of classical antiquity respect ing a class of compositions, which , though they existed then, as in almost every stage of society, were neither so numerous nor of such high repute as to constitute any considerable portion of that literature. Want of space also may entitle us to dismiss the consideration of the Oriental Romances, unless in so far as in the course of the middle ages they came to furnish materials for enlarging and varying the character of the Romances of knight-errantry. That they existed early, and were highly esteemed both among the Persians and Arabians, has never been disputed ; and the most interesting light has been lately thrown on the subject by the publication of Antar, one of the most ancient, as well as most rational, if we may use the phrase, of the Oriental fictions. The Persian Romance of the Sha - Nameh is well known to Europeans by name, and by copious 178 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. extracts ; and the love-tale of Mejnoun and Leilah is also familiar to our ears, if not to our recollec tions. Many of the fictions in the extraordinary collection of the Arabian Tales, that of Codadad and his brethren, for example, approach strictly to the character of Romances of Chivalry ; although in general they must be allowed to exceed the more tame northern fictions in dauntless vivacity of inven tion , and in their more strong tendency to the mar vellous. Several specimens of the Comic Romance are also to be found mingled with those which are serious ; and we have the best and most positive authority that the recital of these seductive fictions is at this moment an amusement as fascinating and general among the people of the East, as the peru sal of printed Romances and novels among the European public. But a minute investigation into this particular species of Romance would lead us from our present field , already sufficiently extensive for the limits to which our plan confines it . The European Romance, wherever it arises, and in whatsoever country it begins to be cultivated, had its origin in some part of the real or fabulous history of that country ; and of this we will produce, in the sequel, abundant proofs. But the simple tale of tradition had not passed through many mouths, ere some one, to indulge his own propensity for the 1 6 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 177 wonderful, or to secure by novelty the attention of his audience, augments the meagre chronicle with his own apocryphal inventions. Skirmishes are ele vated into great battles ; the champion of a remote , age is exaggerated into a sort of demi-god ; and the enemies whom he encountered and subdued are multiplied in number, and magnified in strength , in order to add dignity to his successes against them. Chanted to rhythmical numbers, the songs which celebrate the early valour of the fathers of the tribe become its war- cry in battle, and men march to conflict, hymning the praises and the deeds of some real or supposed precursor who had marshalled their fathers in the path of victory. No reader can have forgotten, that, when the decisive battle of Hastings commenced, a Norman minstrel, Taillefer, advanced on horseback before the inva ding host, and gave the signal for onset, by singing the Song of Roland, that renowned nephew of Charlemagne, of whom Romance speaks so much, and history so little ; and whose fall, with the chi valry of Charles the Great in the pass of Ronces valles, has given rise to such clouds of romantic fic tion, that its very name has been for ever associated with it. The remarkable passage has been often quoted from the Brut of Wace, an Anglo -Norman metrical chronicle. VOL . VI. M 178 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. Taillefer, qui moult bien chantont Sur un cheval gi tost alont, Devant le Duc alont chantant De Karlemaigne et de Rollant, Et d'Oliver et des vassals, Qui morurent en Rencevals. Which may be thus rendered : Taillefer, who sung both well and loud, Came mounted on a courser proud ; Before the Duke the minstrel sprung , And loud of Charles and Roland sung, Of Oliver and champions mo, Who died at fatal Roncevaux. This champion possessed the sleight-of-hand of the juggler, as well as the art of the minstrel. He toss ed up his sword in the air, and caught it again as he galloped to the charge, and showed other feats of dexterity. Taillefer slew two Saxon warriors of distinction, and was himself killed by a third. Rit son , with less than his usual severe accuracy, sup posed that Taillefer sung some part of a long metri cal Romance upon Roland and his history ; but the words chanson, cantilena, and song, by which the composition is usually described, seems rather to apply to a brief ballad or national song ; which is also more consonant with our ideas of the time and place where it was chanted. But neither with these romantic and metrical chronicles did the mind long remain satisfied . More ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 179 details were demanded, and were liberally added by the invention of those who undertook to cater for the public taste in such matters. The same names of kings and champions, which had first caught the national ear, were still retained , in order to secure attention ; and the same assertions of authenticity , and affected references to real history, were stoutly made, both in the commencement and in the course of the narrative. Each nation, as will presently be seen , came at length to adopt to itself a cycle of heroes like those of the Iliad ; a sort of common property to all minstrels who chose to make use of them , under the condition always that the general character ascribed to each individual hero was pre served with some degree of consistency. Thus, in the Romances of The Round Table, Gawain is usually represented as courteous ; Kay as rude and boastful; Mordred as treacherous; and Sir Launce lot as a true though a sinful lover, and in all other respects a model of chivalry. Amid the Paladins of Charlemagne, whose cycle may be considered as peculiarly the property of French in opposition to Norman -Anglo Romance, Gan, or Ganelon of May ence, is always represented as a faithless traitor, engaged in intrigues for the destruction of Christi anity ; Roland as brave, unsuspicious, devotedly loyal, and somewhat simple in his disposition ; 180 ESSAY ON ROMANCE . Renaud, or Rinaldo, who possessed the frontier fortress, is painted with all the properties of a bor derer, valiant, alert, ingenious, rapacious, and un scrupulous. The same conventional distinctions may be traced in the history of the Nibelung, a composition of Scandinavian origin , which has sup plied matter for so many Teutonic Romances. Meis teir Hildebrand, Etzel, Theodorick , and the cham pion Hogan, as well as Chrimhilda and the females introduced, have the same individuality of character, which is ascribed, in Homer's immortal writings,to the wise Ulysses, the brave but relentless Achilles, his more gentle friend Patroclus, Sarpedon the favourite of the gods, and Hector the protector of cm mankind. It was not permitted to the invention of a Greek poet to make Ajax a dwarf, or Teucer a giant, Thersites a hero, or Diomedes a coward ; and it seems to have been under similar restrictions respecting consistency, that the ancient romancers exercised their ingenuity upon the materials sup plied them by their predecessors. But, in other respects, the whole store of romantic history and tradition was free to all as a joint stock in trade, on which each had a right to draw as suited his particular purposes. He was at liberty not only to select a hero out of known and established names which had been the theme of others, but to imagine ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 181 a new personage of his own pure fancy, and com bine him with the heroes of Arthur's Table or Charlemagne's Court, in the way which best suited his fancy. He was permitted to excite new wars against those bulwarks of Christendom, invade them with fresh and innumerable hosts of Saracens, re duce them to the last extremity, drive them from their thrones, and lead them into captivity, and again to relieve their persons, and restore their sovereignty, by events and agents totally unknown in their former story. In the characters thus assigned to the individual personages of romantic fiction , it is possible there might be some slight foundation in remote tradi tion, as there were also probably some real grounds for the existence of such persons, and perhaps for a very few of the leading circumstances attributed to them But these realities only exist as the few grains of wheat in the bushel of chaff, incapable of being winnowed out, or cleared from the mass of fiction with which each new romancer had in his turn overwhelmed them . So that Romance, though certainly deriving its first original from the pure font of History, is supplied, during the course of a very few generations, with so many tributes from the Imagination, that at length the very name comes to be used to distinguish works of pure fiction . 182 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. When so popular a department of poetry has attained this decided character, it becomes time to inquire who were the composers of these numerous, lengthened, and once admired narratives which are called Metrical Romances, and from whence they drew their authority. Both these subjects of dis cussion have been the source of great controversy among antiquarians ; a class ofmen who, be it said with their forgiveness, are apt to be both positive and polemical upon the very points which are least susceptible of proof, and which are least valuable if the truth could be ascertained ; and which , there fore, we would gladly have seen handled with more diffidence, and better temper, in proportion to their uncertainty. The late venerable Dr Percy, Bishop of Dro more, led the way unwarily to this dire controversy, by ascribing the composition of our ancient heroic songs and metrical legends, in rather too liberal language, to the minstrels, that class of men by whom they were generally, recited . This excellent person, to whose memory the lovers of our ancient lyre must always remain so deeply indebted , did not, on publishing his work nearly fifty years ago, see the rigid necessity of observing the utmost and most accurate precision either in his transcripts or his definitions. The study which he wished to ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 183 introduce was a new one — it was his object to place it before the public in an engaging and interesting form ; and, in consideration of his having obtained this important point, we ought to make every allow ance, not only for slight inaccuracies, but for some hasty conclusions, and even exaggerations, with which he was induced to garnish his labour of love. He defined the minstrels, to whose labours he chiefly ascribed the metrical compositions on which he desired to fix the attention of the public, as " an order of men in the middle ages, who subsisted by the arts of poetry and music, and sung to the harp verses composed by themselves or others.” * In a very learned and elegant essay upon the text thus announced, the reverend Prelate in a great measure supported the definition which he had laid down ; although it may be thought that, in the first editions at least, he has been anxious to view the profession of the minstrels on their fairest and most brilliant side ; and to assign to them a higher station in so ciety than a general review of all the passages con nected with them will permit us to give to a class ofpersons, who either lived a vagrant life, depend ent on the precarious taste of the publie for a hard 等 Essay on Ancient Minstrels in England, prefixed to the first volume of Bishop Percy's Reliques. 184 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. earned maintenance, or, at best, were retained as a part of the menial retinue of some haughty baron, and in a great measure identified with his musical band. The late acute, industrious, and ingenious Mr Joseph Ritson, whose severe accuracy was connect ed with an unhappy eagerness and irritability of temper, took advantage of the exaggerations oc casionally to be found in the Bishop's Account of Ancient Minstrelsy, and assailed him with terms which are anything but courteous. Without find ing an excuse, either in the novelty of the studies in which Percy had led the way, or in the viva city of imagination which he did not himself share, he proceeded to arraign each trivial inaccuracy as a gross fraud, and every deduction which he con sidered to be erroneous as a wilful untruth , fit to be stigmatized with the broadest appellation by which falsehood can be distinguished. Yet there is so little room for this extreme loss of temper, that, upon a recent perusal of both those ingenious essays, we were surprised to find that the reverend Editor of the Reliques, and the accurate Antiquary, have differed so very little, as, in essential facts, they ap pear to have done. Quotations are, indeed, made by both with no sparing hand ; and hot arguments, and, on one side at least, hard words, are unsparing ESSAY ON ROMANCE . 185 I ly employed ; while, as is said to happen in theo logical polemics, the contest grows warmer, in pro portion as the ground concerning which it is carried on is narrower and more insignificant. But not withstanding all this ardour of controversy, their systems in reality do not essentially differ. Ritson is chiefly offended at the sweeping con clusion, in which Percy states the minstrels as sub sisting by the arts of poetry and music, and reciting to the harp verses composed by themselves and others. He shows very successfully that this defi nition is considerably too extensive, and that the term minstrel comprehended, of old, not merely those who recited to the harp or other instrument romances and ballads, but others who were distin. guished by their skill in instrumental music only ; and, moreover, that jugglers, sleight-of-hand per formers, dancers, tumblers, and such like subordi. natè artists, who were introduced to help away the tedious hours in an ancient feudal castle, were also comprehended under the general term of minstrel. But although he distinctly proves that Percy's defi nition applied only to one class of the persons term ed minstrels, those namely who sung or recited Verses, and in many cases of their own composition ; the bishop's position remains unassailable, in so far as relates to one general class, and those the most 186 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. distinguished during the middle ages. All min strels did not use the harp, and recite or compose romantic poetry ; but it cannot be denied that such was the occupation of the most eminent of the or der. This Ritson has rather admitted than de nied ; and the number of quotations which his in dustry has brought together, rendered such an ad mission inevitable. Indeed, the slightest acquaintance with ancient Romances of the metrical class, shows us that they were composed for the express purpose of being re cited , or, more properly, chanted , to some simple tune or cadence for the amusement of a large audi ence. Our ancestors, as they were circumscribed in knowledge, were also more limited in conversational powers than their enlightened descendants ; and it seems probable, that, in their public festivals, there was great advantage found in the presence of a min-. strel, who should recite some popular composition on their favourite subjects of love and war, to pre vent those pauses of discourse which sometimes fall heavily on a company, even of the present ac complished age, and to supply an agreeable train of ideas to those guests who had few of their own. It is, therefore, almost constantly insinuated , that the Romance was to be chanted or recited to a large and festive society, and in some part or other ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 187 of the piece, generally at the opening, there is a request of attention on the part of the performer ; and hence, the perpetual “ Lythe and listen, lord ings free,” which in those, or equivalent words, forms the introduction to so many Romances. As, for example, in the old poem of Guy and Colbrand, the minstrel speaks of his own occupation : “ When meat and drink is great plentye, Then lords and ladyes still will be, And sit and solace lythe. Then it is time for mee to speake, Of kern knights and kempes greate, Such carping for to kythe.” Chaucer, also , in his Ryme of Sir Thopas, assigns to the minstrels of his hero's household the same duty, of reciting Romances of spiritual or secular heroes, for the good knight's pastime while arming for battle : “ Do cum , " he sayd, “ my minestrales, And jestours for to tellen tales Anon in min arming, Of romaunces that ben reales, Of popes and of cardinales, And eke of love- longing." Not to multiply quotations, we will only add one of some importance, which must have escaped Rit son's researches ; for his editorial integrity was such, as rendered him incapable of suppressing evidence on either side of the question. In the old Romance 188 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. or legend of True Thomas and the Queen ofEl land, Thomas the Rhymer, himself a minstrel, is gifted by the Queen of the Faery with the facul ties of music and song. The answer of Thomas is not only conclusive as to the minstrel's custom of recitation , but shows that it was esteemed the high est branch of his profession, and superior as such to mere instrumental music : “ To harp and carp, Thomas, wheresover ye gon, Thomas take the these with the ” . “ Harping, ” he said, “ ken I non, Fortong is chefe of Mynstralse.' We, therefore, arrive at the legitimate conclusion , that although, under the general term minstrels, were comprehended many who probably entertained the public onlywith instrumental performances, with ribald tales, with jugglery, or farcical representa tions, yet one class amongst them , and that a nu merous one, made poetical recitations their chief, if not their exclusive occupation. The memory of these men was, in the general case, the depository of the pieces which they recited ; and hence, al though a number of their Romances still survive, very many more have doubtless fallen into oblivion .

- Jamieson's Popular Ballads, vol . II . p. 27.

ESSAY ON ROMANCE . 189 That the minstrels were also the authors of many of these poems, and that they altered and enlarged others, is a matter which can scarce be doubted, when it is proved that they were the ordinary re citers of them . It was as natural for a minstrel to become a poet' or composer of Romances, as for a player to be a dramatic author, or a musician a com poser of music. Whatsoever individual among a class, whose trade it was to recite poetry, felt the least degree of poetical enthusiasm in a profession so peculiarly calculated to inspire it, must, from that very impulse, have become an original author, or translator at least : thus giving novelty to his recitations, and acquiring additional profit and fame. Bishop Percy, therefore, states the case fairly in the following passage :- “ It can hardly be expect ed, that we should be able to produce regular and unbroken annals of the minstrel art and its profess ors, or have sufficient information , whether every minstrel or bard composed himself, or only repeated, the songs he chanted . Some probably did the one, and some the other ; and it would have been won derful, indeed, if men, whose peculiar profession it was, and who devoted their time and talents to entertain their hearers with poetical compositions, were peculiarly deprived of all poetical genius them selves, and had been under a physical incapacity of 190 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. composing those common popular rhymes, which were the usual subjects of their recitation . " * While, however, we acquiesce in the proposition, that the minstrels composed many, perhaps the greater part, of the metrical Romances which they sung, it is evident they were frequently assisted in the task by others, who, though not belonging to this pro fession , were prompted by leisure and inclination to enter upon the literary or poetical department as amateurs. These very often belonged to the cleri cal profession, amongst whom relaxation of disci pline, abundance of spare time, and impatience ofthe routine of ceremonious duties, often led individuals into worse occupations than the listening to or com posing metrical Romances. It was in vain that both the poems and the minstrels who recited them were, by statutę, debarred from entering the more rigid monasteries. Both found their way frequent Essay on the Ancient Minstrels, p. 30. Another authority of ancient date, the Chronicle of Bertrand Guesclin , distinctly attributes the most renowned Romances to the composition of the minstrels by whom they were sung. As the passage will be afterwards more fully quoted, we must here only say, that after enumerating Arthur, Lancelot, Godfrey, Ro land, and other champions, he sums up his account of them as being the heroes “ De quoi cils minestriers font les nobles romans . ” ESSAY ON ROMANCE . 191 ly to the refectory, and were made more welcome than brethren of their own profession ; as we may learn from a memorable Gest, in which two poor travelling priests, who had been received into a monastery with acclamation, under the mistaken idea of their being minstrels, are turned out in dis grace, when it is discovered that they were indeed capable of furnishing spiritual instruction, but un derstood none of the entertaining arts with which the hospitality of their hosts might have been re paid by itinerant bards. Nay, besides a truant disposition to a forbidden task , many of the grave authors may have alleged, in their own defence, that the connexion between history and Romance was not in their day entirely dissolved. Some eminent men exercised themselves in both kinds of composition ; as, for example, Maitre Wace, a canon of Caen, in Normandy, who, besides the metrical chronicle of La Brut, contain ing the earliest history of England, and other his torical legends, wrote in 1155, the Roman de Che valier de Lyon, probably the same translated un der the title of Ywain and Gawain . Lambert li Cors, and Benoit de Saint-Maur, seem both to have been of the clerical order ; and, perhaps, Chretien de Troyes, a most voluminous author of Romance, was of the same profession. Indeed, the extreme 192 ESSAY ON ROMANCE . length of many Romances being much greater than any minstrel could undertake to sing at one or even many sittings, may induce us to refer them to men of a more sedentary occupation than those wander ing poets. The religious Romances were, in all probability, the works of such churchmen as might wish to reconcile an agreeable occupation with their religious profession . All which circumstances must be received as exceptions from the general proposi tion, that the Romances in metre were the compo sition of the minstrels by whom they were recited or sung, though they must still leave Percy's pro position to a certain extent unimpeached. To explain the history of Romance, it is neces sary to digress a little farther concerning the con dition of the minstrels by whom these compositions were often made, and, generally speaking, preser ved and recited. And here it must be confessed , that the venerable Prelate has, perhaps, suffered his love of antiquity, and his desire to ennoble the pro ductions of the middle ages, a little to overcolour the importance and respectability of the minstrel tribe ; although his opponent Ritson has, on the other hand, seized on all circumstances and infer ences which could be adduced to prove the degra dation of the minstrel character, without attending to the particulars by which these depreciating cir 13 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 193 cumstances were qualified. In fact, neither of these excellent antiquarians has cast a general or philoso phic glance on the necessary condition of a set of men , who were by profession the instruments of the pleasure of others during a period of society such as was presented in the middle ages. In a very early period of civilization , ere the divi sion of ranks has been generally adopted, and while each tribe may be yet considered as one great fa mily, and the nation as a union of such independent tribes, the poetical art, so nearly allied to that of ora tory or persuasion, is found to ascertain to its profess ors a very high rank . Poets are, then, the historians and often the priests of the society. Their com mand of language, then in its infancy, excites not merely pleasure, but enthusiasm and admiration. When separated into a distinct class, as was the case with the Celtic Bards, and, perhaps, with the Skalds of Scandinavia , they rank high in the scale of society, and we not only find kings and nobles listening to them with admiration, but emulous of their art, and desirous to be enrolled among their numbers. Several of the most renowned northern kings and champions valued themselves as much upon their powers of poetry as on their martial ex ploits ; and of the Welsh princes, the Irish kings, and the Highland chiefs of Scotland, very many VOL . VI. N 194 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. | practised the arts of poetry and music. Llwarch Hen was a prince of the Cymraig, Brian Bo romhe, a harper and a musician ,-and, without re sorting to the questionable authenticity of Ossian, several instances of the same kind might be produ ced in the Highlands. But, in process of time, when the classes of so ciety come to assume their usual gradation with re spect to each other, the rank of professional poets is uniformly found to sink gradually in the scale, along with that of all others whose trade it is to contribute to mere amusement. The profes sional poet, like the player or the musician, be comes the companion and soother only of idle and convivial hours ; his presence would be unbecoming on occasions of gravity and importance ; and his art is accounted at best an amusing but useless luxury. Although the intellectual pleasure deri ved from poetry, or from the exhibition of the dra ma, be of a different and much higher class than that derived from the accordance of sounds, or from the exhibition of feats of dexterity, still it will be found, that the opinions and often the laws of so ciety, while individuals of these classes are cherish ed and held in the highest estimation , have de graded the professions themselves among its idle, dissolute, and useless appendages. Although it may ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 195 be accounted ungrateful in mankind thus to re ward the instruments of their highest enjoyments, yet some justification is usually to be drawn from the manners of the classes who were thus lowered in public opinion. It must be remembered, that, as professors of this joyous science, as it was called, the minstrels stood in direct opposition to the more severe part of the Catholics, and to the monks in particular, whose vows bound them to practise vir tues of the ascetic order, and to look upon every thing as profane, which was connected with mere worldly pleasure. The manners of the minstrels themselves gave but too much room for clerical cen sure. They were the usual assistants at scenes, not merely of conviviality, but of licence ; and, as the companions and encouragers of revelling and excess, they became contemptible in the eyes, not only of the aged and the serious, but of the libertine him self, when his debauch palled on his recollection. The minstrels, no doubt, like their brethren of the stage, sought an apology in the corrupted taste and manners of their audience, with which they were obliged to comply, under the true but melan choly condition, that they who live to please must please to live. But this very necessity, rendered more degrading 196 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. by their increasing numbers and decreasing repu tation , only accelerated the total downfall of their order, and the general discredit and neglect into which they had fallen . The statute of the 39th of Queen Elizabeth, passed at the close of the six teenth century, ranks those dishonoured sons of song among rogues and vagabonds, and appoints them to be punished as such ; and the occupation, though a vestige of it was long retained in the habits of travelling ballad - singers and musicians, sunk into total neglect and contempt. Of this we shall have to speak hereafter ; our business being at present with those Romances, which, while still in the zenith of their reputation, were the means by which the minstrels, at least the better and higher class among them , recommended themselves to the favour of their noble patrons, and of the audiences whom they addressed. It may be presumed, that, although the class of minstrels, like all who merely depend upon gratify ing the public, carried in their very occupation the evils which first infected, and finally altogether der praved, their reputation ; yet, in the earlier ages, their duties were more honourably estimated , and some attempts were made to introduce into their motley body the character of a regular establish ment, subjected to discipline and subordination . ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 197 what all this concern with behavior of Minstrels Several individuals, both of France and England, bore the title of King of Minstrels, and were in vested probably with some authority over the others. The Serjeant of Minstrels is also mentioned ; and Edward IV. seems to have attempted to form a Guild or exclusive Corporation of Minstrels. John of Gaunt, at an earlier period, established ( between jest and earnest, perhaps) a.Court Baron of Min strels, to be held at Tilbury. There is no reason , however, to suppose, that the influence of their esta blishments went far in restraining the licence of a body of artists so unruly as well as numerous. It is not, indeed, surprising that individuals, whose talents in the arts of music, or of the stage, rise to the highest order, should, in a special degree, attain the regardand affection of the powerful, ac quire wealth, and rise to consideration ; for, in such professions, very high prizes are assigned only to pre eminent excellence ; while ordinary or inferior prac tisers of the same art may be said to draw in the lottery something worse than a mere blank. In the useful arts, a great equality subsists among the mem bers, and it is wealth alone which distinguishes a tradesman or a mechanic from the brethren of his guild ; in other points their respectability is equal. The worst weaver in the craft is still a weaver, and the best, to all but those who buy his web, is little 198 ESSAY ON ROMANCE . móre - as men they are entirely on a level. In what are called the fine arts, it is different; for excellence leads to the highest point of consideration ; medio crity, and marked inferiority, are the object of neglect and utter contempt. Garrick, in his chariot, and whose company was courted for his wit and talent, was, after all, by profession, the same with the unfor tunate stroller, whom the British laws condemn as a vagabond, and to whose dead body other countries refuse even the last rites of Christianity. In the same manner it is easy to suppose, that when, in compliance with the taste of their age, monarchs entertained their domestic minstrels,* those persons might be admitted to the most flattering intimacy with their royal masters ; sleep within the royal chamber, † amass considerable fortunes, found hos pitals, f and receive rewards singularly over-propor

- Berdic ( Regis Joculator ), the jongleur or minstrel of Wil

liam the Conqueror, bad, as appears from the Domesday record, three vills and five caracates of land in Gloucestershire without rent. Henry I. had a minstrel called Galfrid who received an annuity from the Abbey of Hide. + A minstrel of Edward I., during that prince's expedition to the Holy Land, slept within his tent, and came to his assistance when an attempt was made to assassinate him. | The Priory and Hospital of Saint Bartholomew , in London, was founded in the reign of Henry I. by Royer, or Raher, a min Strel of that prince. ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 199 tioned to the perquisites of the graver professions ; * and even practise, in company with their royal mas ters, the pleasing arts of poetry and music, which all are so desirous of attaining ; † whilst, at the same time, those who ranked lower in the same profession were struggling with difficulty to gain a precarious subsistence, and many, of a rank still more subordi nate, were incurring all the disgrace usually attach ed to a vagabond life and a dubious character. In the fine arts, we repeat, excellence is demanded, and mere mediocrity is held contemptible ; and, while the favour with which the former is loaded , sometimes seems disproportioned to the utility of the art itself, nothing can exceed the scorn poured out on those who expose themselves by undertaking arts which they are unable to practise with success ; and it follows, that as excellence can only be the property of a few individuals, the profession in ge neral must be regarded as a degraded one, though these gifted persons are allowed to pass as eminent

- In 1441 , the monks of Maxlock, near Coventry, paid a do

nation of four shillings to the minstrels of Lord Clinton for songs, harping, and other exhibitions, while, to a doctor who preached before the community in the same year, they assigned only six pence. + The noted anecdote of Blondel and his royal master, Rich ard Cæur de Lion, will occur to every reader. 200 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. exceptions to the general rule. Self-conceit, how ever, love of an idle life, and a variety of combined motives, never fail to recruit the lower orders of such idle professions with individuals, by whose per formances, and often by their private characters, the art which they have rashly adopted is discredited, without any corresponding advantage to themselves. It is not, therefore, surprising, that while such distinguished examples of the contrary appeared amongst individuals, the whole body of minstrels, with the Romances which they composed and sung, should be reprobated by graver historians in such severe terms as often occur in the monkish chro nicles of the day. Respecting the style of their composition, Du Cange informs us, that the minstrels sometimes de voted their strains to flatter the great, and sing the praises of those Princes by whom they were protect ed ; while he owns, at the same time, that they often recommended to their hearers the path of vir tue and nobleness, and pointed out the pursuits by which the heroes of Romance had rendered them selves renowned in song. He quotes from the

- MINISTELLI dicti præsertim Scurræ , mimi, joculatores,

quos etiamnum vulgo Menestreux vel Menestriers, appellamus. -Porro ejusmodi scurrarum erat Principes non suis duntaxat lu ESSAY ON ROMANCE . 201 Romance of Bertrand Guesclin, the injunction on those who would rise to fame in arms to copy the valiant acts of the Paladins of Charles, and the Knights of the Round Table, narrated in Roman ces ; and it cannot be denied, that those high tales, in which the virtues of generosity, bravery, devo tion to his mistress, and zeal for the Catholic reli gion, were carried to the greatest height of roman tic perfection in the character of the hero, united with the scenes passing around them , were of the utmost importance in affecting the character of the X dicris oblectare, sed et eorum aures variis avorum , adeoque ipso rum Principum laudibus, non sine assentatione, cum cantilenis et musicis instrumentis, demulcere.Interdum etiam virorum insignium et heroum gesta, aut explicata et jucunda narratione commemorabant, aut suavi vocis inflectione, fidibusque decanta bant, quo sic dominorum , cæterorumque qui his intererant ludi cris, nobilium animos ad virtutem capessendam et summorum virorum imitationem accenderent : quod fuit olim apud Gallos Bardorum ministerium , ut auctor est Tacitus. Neque enim alios à Ministellis, veterum Gallorum Bardos fuisse pluribus probat Henricus Valesius ad 15. Ammiani. - Chronicon BertrandiGues clini : Qui veut avoir renom des bons et des vaillans Ill doit aler souvent à la pluie et au champ, Et estre en la bataille, ainsy quefu Rollans, Les quatre fils Haimon et Charlon li plus grans, Li Dus Lions de Bourges, et Guion de Connans, Perceval li Galois, Lancelot et Tristans, Alexandres, Artus, Godefroy li sachans, De quoy cils Menestriers font les nobles Romans. 202 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. | age. The fabulous knights of Romance were so completely identified with those of real history, that graver historians quote the actions of the former in illustration of, and as a corollary to, the real events which they narrate. * The virtues recommended in Romance were, however, only of that overstrained and extravagant cast which consisted with the spirit of chivalry. Great bodily strength, and perfection X in all martial exercises, was the universal accom plishment inalienable from the character of the hero, and which each romancer had it in his power to confer. It was also easily in the composer's power to devise dangers, and to free his hero from them by the exertion of valour equally extravagant. But it was more difficult to frame a story which should illustrate the manners as well as the feats of Chi valry ; or to devise the means of evincing that de votion to duty, and that disinterested desire to sa crifice all to faith and honour ; —that noble spirit of achievement which laboured for others more than itself — which form , perhaps, the fairest side of the system under which the noble youths of the middle X Х

- Barbour, the Scottish historian, censures a Highland chief,

when, in commending the prowess of Bruce in battle, he likened him to the Celtic hero, Fin Mac Coul, and says, he might in more mannerly fashion have compared him to Gaudifer, a champion celebrated in the Romance of Alexander. ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 203 ages were trained up. The sentiments of Chivalry, as we have explained in our article on that subject, were founded on the most pure and honourable prin ciples, but unfortunately carried into hyperbole and extravagance ; until the religion of its professors approached to fanaticism , their valour to frenzy, their ideas of honour to absurdity, their spirit of en terprise to extravagance, and their respect for the female sex to a sort of idolatry. All those extra vagant feelings, which really existed in the society of the middle ages, were magnified and exaggera ted by the writers and reciters of Romance ; and these, given as resemblances of actual manners, be came, in their turn , the glass by which the youth of the age dressed themselves; while the spirit of Chivalry and of Romance thus gradually threw light upon and enhanced each other. The Romances, therefore, exhibited the same sys tem of manners which existed in the nobles of the age. The character of a true son of chivalry was raised to such a pitch of ideal and impossible per fection, that those who emulated such renown were usually contented to stop far short of the mark. The most adventurous and unshaken valour, a mind capable of the highest flights of romantic generosity, a heart which was devoted to the will of some fair idol, on whom his deeds were to reflect 204 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. glory, and whose love was to reward all his toils--- these were attributes which all aspired to exhibit who sought to rank high in the annals of chivalry ; and such were the virtues which the minstrels cele brated . But, like the temper of a tamed lion, the fierce and dissolute spirit of the age often showed itself through the fair varnish of this artificial sys tem of manners. The valour of the hero was often stained by acts of cruelty, or freaks of rash despera tion ; his courtesy and munificence became solemn foppery and wild profusión ; his love to his lady often demanded and received a requital inconsistent with the honour of the object ; and those who affected to found their attachment on the purest and most delicate metaphysical principles, carried on their actual intercourse with a licence altogether inconsistent with their sublime pretensions. Such were the real manners of the middle ages, and we find them so depicted in these ancient legends. So high was the national excitation in conse quence of the romantic atmosphere in which they seemed to breathe, that the knights and squires of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries imitated the wildest and most extravagant emprises of the heroes of Romance ; and, like them , took on themselves the most extraordinary adventures, to show their own gallantry, and do most honour to the ladies of X ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 205 their hearts. The females of rank, erected into a species of goddesses in public, and often degraded as much below their proper dignity in more pri vate intercourse, equalled in their extravagances the youth of the other sex. A singular picture is given by Knyghton of the damsels- errant who attended upon the solemn festivals of chivalry, in quest, it may reasonably be supposed, of such adventures as are very likely to be met with by such females as think proper to seek them. " These tournaments are attended by many ladies of the first rank and greatest beauty, but not always of the most untaint ed reputation. These ladies are dressed in party coloured tunics, one -half of one colour, and the other half of another ; their lirripipes, or tippets, are very short ; their caps remarkably little, and wrapt about their heads with cords ; their girdles and pouches are ornamented with gold and silver ; and they wear short swords, called daggers, before them , a little below their navels ; they are mounted on the finest horses, with the richest furniture. Thus equipped, they ride from place to place in quest of tournaments, by which they dissipate their fortunes, and sometimes ruin their reputation." - (Knyghton , quoted in Henry's History, vol. VIII. p. 402. ) The minstrels, or those who aided them in the composition of the Romances, which it was their tomboys ? 206 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. profession to recite, roused to rivalry by the uncea sing demand for their compositions, endeavoured emulously to render them more attractive by sub jects of new and varied interest, or by marvellous incidents which their predecessors were strangers to. Much labour has been bestowed, somewhat unpro fitably, in endeavouring to ascertain the sources from which they drew the embellishments of their tales, when the hearers began to be tired of the unvaried recital of battle and tournament which had satisfied the simplicity of a former age. Percy has contended for the Northern Sagas as the un questionable origin of the Romance of the middle ages ; Warton conceived that the Oriental fables, borrowed by those minstrels who visited Spain, or who in great numbers attended the crusades, gave the principal distinctive colouring to those remark able compositions ; and a later system, patronised by later authors, has derived them , in a great mea sure, from the Fragments of ClassicalSuperstition, which continued to be preserved after the fall of the Roman Empire. All those systems seem to be inaccurate, in so far as they have been adopted, exclusively of each other, and of the general propo sition , That fables of a nature similar to the Ro mances of Chivalry, modified according to manners and state of society, must necessarily be invented in 1 ESSAY ON ROMANCE. 207 every part of the world, for the same reason that grass grows upon the surface of the soil in every climate and in every country. “ In reality ,” says! Mr Southey, who has treated this subject with his usual ability, “ mythological and romantic tales are current among all savages of whom we have any full account ; for man has his intellectual as well as his bodily appetites, and these things are the food of his imagination and faith . They are found where ever there is language and discourse of reason, in other words, wherever there is man. And in simi lar stages of civilization, or states of society, the fic tions of different people will bear a corresponding resemblance, notwithstanding the difference of time and scene. ” * To this it may be added, that the usual appear ances and productions of nature offer to the fancy, in every part of the world, the same means of diver sifying fictitious narrative by the introduction of prodigies. If in any Romance we encounter the description of an elephant, we may reasonably con clude that a phenomenon , unknown in Europe, must have been borrowed from the east ; but whosoever has seen a serpent and a bird, may easily aggravate