Idealism

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 15:46, 27 November 2014 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 15:47, 27 November 2014 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) Next diff → |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| - | '''Idealism''' is the philosophical theory which maintains that [[experience]] is [[The Ultimate|ultimately]] based on mental activity. In the [[philosophy of perception]], idealism is contrasted with [[Philosophical realism|realism]], in which the external world is said to have an apparent [[absolute]] [[existence]]. [[Epistemology|Epistemological]] idealists (such as [[Kant]]) claim that the only things which can be directly ''known for certain'' are just ideas ([[abstraction]]). In literature, idealism refers to the thoughts or the ideas of the writer. | + | In [[philosophy]], '''idealism''' is the group of philosophies which assert that reality, or reality as we can know it, is fundamentally mental, mentally constructed, or otherwise immaterial. [[Epistemology|Epistemologically]], idealism manifests as a [[skepticism]] about the possibility of knowing any mind-independent thing. In a sociological sense, idealism emphasizes how human ideas—especially beliefs and values—shape society. As an [[ontology|ontological]] doctrine, idealism goes further, asserting that all entities are composed of mind or spirit. Idealism thus rejects [[physicalism|physicalist]] and [[dualism (philosophy of mind)|dualist]] theories that fail to ascribe priority to the mind. |

| + | |||

| + | The earliest extant arguments that the world of experience is grounded in the mental derive from India and Greece. The [[Hindu idealism|Hindu idealists]] in India and the Greek [[Neoplatonism|Neoplatonists]] gave [[panentheism|panentheistic]] arguments for an all-pervading consciousness as the ground or true nature of reality. In contrast, the [[Yogacara|Yogācāra]] school, which arose within [[Mahayana]] Buddhism in India in the 4th century CE, based its "mind-only" idealism to a greater extent on [[Phenomenology (philosophy)|phenomenological]] analyses of personal experience. This turn toward the [[subjective idealism|subjective]] anticipated [[empiricism|empiricists]] such as [[George Berkeley]], who revived idealism in 18th-century Europe by employing skeptical arguments against [[materialism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Beginning with [[Immanuel Kant]], [[German idealism|German idealists]] such as [[G. W. F. Hegel]], [[Johann Gottlieb Fichte]], [[Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling]], and [[Arthur Schopenhauer]] dominated 19th-century philosophy. This tradition, which emphasized the mental or "ideal" character of all phenomena, birthed idealistic and [[subjectivism|subjectivist]] schools ranging from [[British idealism]] to [[phenomenalism]] to [[existentialism]]. The historical influence of this branch of idealism remains central even to the schools that rejected its [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] assumptions, such as [[Marxism]], [[pragmatism]] and [[positivism]]. | ||

| - | In the [[philosophy of mind]], idealism is the opposite of [[materialism]], in which the ultimate nature of reality is based on physical substances. Materialism is a theory of [[monism]] as opposed to [[dualism (philosophy of mind)|dualism]] and [[pluralism (metaphysics)|pluralism]], while idealism might or might not be monistic. Hence, idealism can take dualistic form and often does, since the subject-object division is dualistic by definition. Idealism sometimes refers to a tradition in thought that represents things of a perfect form, as in the fields of ethics, morality, aesthetics, and value. In this way, it represents a human perfect being or circumstance. | ||

| - | Idealism is a philosophical movement in Western thought, but is not entirely limited to the West, and names a number of philosophical positions with sometimes quite different tendencies and implications in politics and ethics; for instance, at least in popular culture, philosophical idealism is associated with Plato and the school of platonism. | ||

| ==Other uses==<!-- This section is linked from [[Old Harry's Game]] --> | ==Other uses==<!-- This section is linked from [[Old Harry's Game]] --> | ||

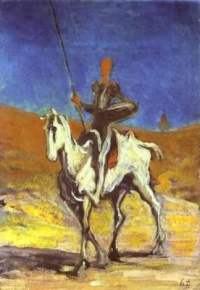

| In general parlance, "idealism" or "idealist" is also used to describe a person having high [[ideal (ethics)|ideals]], sometimes with the connotation that those ideals are unrealisable or at odds with "practical" life, or naively at variance with empirical observations of the real world. | In general parlance, "idealism" or "idealist" is also used to describe a person having high [[ideal (ethics)|ideals]], sometimes with the connotation that those ideals are unrealisable or at odds with "practical" life, or naively at variance with empirical observations of the real world. | ||

Revision as of 15:47, 27 November 2014

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

In philosophy, idealism is the group of philosophies which assert that reality, or reality as we can know it, is fundamentally mental, mentally constructed, or otherwise immaterial. Epistemologically, idealism manifests as a skepticism about the possibility of knowing any mind-independent thing. In a sociological sense, idealism emphasizes how human ideas—especially beliefs and values—shape society. As an ontological doctrine, idealism goes further, asserting that all entities are composed of mind or spirit. Idealism thus rejects physicalist and dualist theories that fail to ascribe priority to the mind.

The earliest extant arguments that the world of experience is grounded in the mental derive from India and Greece. The Hindu idealists in India and the Greek Neoplatonists gave panentheistic arguments for an all-pervading consciousness as the ground or true nature of reality. In contrast, the Yogācāra school, which arose within Mahayana Buddhism in India in the 4th century CE, based its "mind-only" idealism to a greater extent on phenomenological analyses of personal experience. This turn toward the subjective anticipated empiricists such as George Berkeley, who revived idealism in 18th-century Europe by employing skeptical arguments against materialism.

Beginning with Immanuel Kant, German idealists such as G. W. F. Hegel, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, and Arthur Schopenhauer dominated 19th-century philosophy. This tradition, which emphasized the mental or "ideal" character of all phenomena, birthed idealistic and subjectivist schools ranging from British idealism to phenomenalism to existentialism. The historical influence of this branch of idealism remains central even to the schools that rejected its metaphysical assumptions, such as Marxism, pragmatism and positivism.

Other uses

In general parlance, "idealism" or "idealist" is also used to describe a person having high ideals, sometimes with the connotation that those ideals are unrealisable or at odds with "practical" life, or naively at variance with empirical observations of the real world.

The word "ideal" is commonly used as an adjective to designate qualities of perfection, desirability, and excellence. This is foreign to the epistemological use of the word "idealism" which pertains to internal mental representations. These internal ideas represent objects that are assumed to exist outside of the mind.

See also

- Idea

- Ideal

- Palais idéal by facteur Cheval

- Perfection