Animal

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 11:39, 6 January 2008 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Image:Un Chat Angola.jpg|thumb|left|200px|''[[Un chat Angola qui guette un oiseau]]'' [[1861]] by [[Jean-Jacques Bachelier]]]] | ||

| + | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| + | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| + | "It is only natural that the two most prominent [[animal]] figures in the [[Mythology |mythical]] heaven should be the [[cow]] and the [[Sacred bull |bull]]."--''[[Zoological Mythology, Or The Legends of Animals]]'' (1872) by Angelo De Gubernatis | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "When he is dominated by [[sexual desire]], he will believe everything you happen to tell him. Knock on a stone with your fingernail - in his own [[morse code]] - and at once he answers."--''[[The Soul of the White Ant]]'' (1925) by Eugène Marais | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "[[omne animal post coitum triste]]" | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "It was in the [[Orient]], too, that [[mythical]] and [[symbolical]] [[zoology]], as the natural outgrowth of the doctrine of [[metempsychosis]], attained its most exuberant development. The [[monstrosities]] of Indian, Assyrian, Egyptian, and archaic Greek art, [[sphinx]]es, [[centaur]]s, [[minotaur]]s, [[human-headed bull]]s, [[lion-headed]] kings, [[horse-headed]] goddesses, and [[sparrow-headed gods]], are all the plastic embodiments of this [[metaphysical]] tenet. The same notion finds expression in [[heraldry]], where real and fabulous [[animal]]s are blazoned in whimsical devices on [[coats-of-arms]] and [[ensign]]s as [[emblem]]s of qualities supposed to be peculiar to individuals- or hereditary in families."--''[[Animal Symbolism in Ecclesiastical Architecture]]'' (1896) by E. P. Evans | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | [[Image:The Experts, 1837 by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps.jpg |thumb|200px|''[[The Experts]]'' ([[1837]]) by [[Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps]]]] | ||

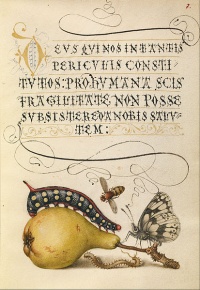

| + | [[Image:Fly, Caterpillar, Pear, and Centipede is the informal title for one page from the Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta by Joris Hoefnagel..jpg|thumb|right|200px|''[[Fly, Caterpillar, Pear, and Centipede]]'' from the ''Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta'' by Joris Hoefnagel]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Chimpanzee Typing (1907) - New York Zoological Society.jpg|thumb|200px|''[[Chimpanzee Typing]]'' (1907) - New York Zoological Society]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Daniel Hopfer.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Grotesque]] [[animal]]s by [[Daniel Hopfer]]]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Audubon.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''[[The Birds of America]]'' (1836) by John James Audubon]] | ||

| + | |||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| - | The word "animal" comes from the [[Latin]] word ''animal'', of which ''animalia'' is the plural, and is derived from ''anima'', meaning vital [[breath]] or [[soul]]. In everyday colloquial usage, the word usually refers to [[non-human]] animals. The biological definition of the word refers to all members of the Kingdom Animalia. Therefore, when the word "animal" is used in a biological context, [[human]]s are included. | + | The word "[[animal]]" comes from the [[Latin]] word ''animal'', of which ''animalia'' is the plural, and is derived from ''[[anima]]'', meaning vital [[breath]] or [[soul]]. In everyday colloquial usage, the word usually refers to [[non-human]] animals. The biological definition of the word refers to all members of the Kingdom Animalia. Therefore, when the word "animal" is used in a biological context, [[human]]s are included. |

| + | ==History of classification== | ||

| + | [[Aristotle]] divided the living world between animals and [[plant]]s, and this was followed by [[Carolus Linnaeus]] (Carl von Linné), in the first hierarchical classification. Since then biologists have begun emphasizing evolutionary relationships, and so these groups have been restricted somewhat. For instance, microscopic [[protozoa]] were originally considered animals because they move, but are now treated separately. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[Carolus Linnaeus|Linnaeus]]'s original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of [[Vermes]], [[Insect]]a, [[Fish|Pisces]], [[Amphibia]], [[bird|Aves]], and [[Mammal]]ia. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the [[chordate|Chordata]], whereas the various other forms have been separated out. The above lists represent our current understanding of the group, though there is some variation from source to source. | ||

| + | ==Consciousness== | ||

| + | :''[[animal cognition]]'' | ||

| + | The sense in which animals can be said to have [[consciousness]] or a [[self-concept]] has been hotly debated; it is often referred to as the debate over [[animal mind]]s. The best known research technique in this area is the [[mirror test]] devised by [[Gordon G. Gallup]], in which an animal's skin is marked in some way while it is asleep or sedated, and it is then allowed to see its reflection in a mirror; if the animal spontaneously directs grooming behavior towards the mark, that is taken as an indication that it is aware of itself. Self-awareness, by this criterion, has been reported for chimpanzees and also for other great apes, the [[European Magpie]], some [[cetaceans]] and a solitary [[elephant]], but not for monkeys. The mirror test has attracted controversy among some researchers because it is entirely focused on vision, the primary sense in humans, while other species rely more heavily on other senses such as the [[olfactory]] sense in dogs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A different approach to determine whether a non-human animal is conscious derives from passive speech research with a macaw (see [[Talking Birds#Arielle|Arielle]]). Some researchers propose that by passively listening to an animal's voluntary speech, it is possible to learn about the thoughts of another creature and to determine that the speaker is conscious. This type of research was originally used to investigate a child's [[crib talk|crib speech]] by Weir (1962) and in investigations of early speech in children by Greenfield and others (1976). With speech-capable birds, the methods of passive-speech research open a new avenue for investigation. | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| + | *[[Animal culture]] | ||

| + | *[[Animal cognition]] | ||

| + | *[[Animal sexual behaviour]] | ||

| + | *[[Animal tale]] | ||

| + | *[[Animal trial]] | ||

| *[[Anthropomorphism]] | *[[Anthropomorphism]] | ||

| + | *[[Herd behavior ]] | ||

| + | *[[Mammal]] | ||

| + | *[[Non-human]] | ||

| *[[Stereotypes of animals]] | *[[Stereotypes of animals]] | ||

| + | *[[Talking animals in fiction]] | ||

| + | *[[Ugly animal]] | ||

| + | *[[Zoomorphism]] | ||

| + | *[[Structures built by animals]] | ||

| + | *[[Tool use by animals]] | ||

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

Current revision

|

"It is only natural that the two most prominent animal figures in the mythical heaven should be the cow and the bull."--Zoological Mythology, Or The Legends of Animals (1872) by Angelo De Gubernatis "When he is dominated by sexual desire, he will believe everything you happen to tell him. Knock on a stone with your fingernail - in his own morse code - and at once he answers."--The Soul of the White Ant (1925) by Eugène Marais "omne animal post coitum triste" "It was in the Orient, too, that mythical and symbolical zoology, as the natural outgrowth of the doctrine of metempsychosis, attained its most exuberant development. The monstrosities of Indian, Assyrian, Egyptian, and archaic Greek art, sphinxes, centaurs, minotaurs, human-headed bulls, lion-headed kings, horse-headed goddesses, and sparrow-headed gods, are all the plastic embodiments of this metaphysical tenet. The same notion finds expression in heraldry, where real and fabulous animals are blazoned in whimsical devices on coats-of-arms and ensigns as emblems of qualities supposed to be peculiar to individuals- or hereditary in families."--Animal Symbolism in Ecclesiastical Architecture (1896) by E. P. Evans |

_-_New_York_Zoological_Society.jpg)

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

The word "animal" comes from the Latin word animal, of which animalia is the plural, and is derived from anima, meaning vital breath or soul. In everyday colloquial usage, the word usually refers to non-human animals. The biological definition of the word refers to all members of the Kingdom Animalia. Therefore, when the word "animal" is used in a biological context, humans are included.

History of classification

Aristotle divided the living world between animals and plants, and this was followed by Carolus Linnaeus (Carl von Linné), in the first hierarchical classification. Since then biologists have begun emphasizing evolutionary relationships, and so these groups have been restricted somewhat. For instance, microscopic protozoa were originally considered animals because they move, but are now treated separately.

In Linnaeus's original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of Vermes, Insecta, Pisces, Amphibia, Aves, and Mammalia. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the Chordata, whereas the various other forms have been separated out. The above lists represent our current understanding of the group, though there is some variation from source to source.

Consciousness

The sense in which animals can be said to have consciousness or a self-concept has been hotly debated; it is often referred to as the debate over animal minds. The best known research technique in this area is the mirror test devised by Gordon G. Gallup, in which an animal's skin is marked in some way while it is asleep or sedated, and it is then allowed to see its reflection in a mirror; if the animal spontaneously directs grooming behavior towards the mark, that is taken as an indication that it is aware of itself. Self-awareness, by this criterion, has been reported for chimpanzees and also for other great apes, the European Magpie, some cetaceans and a solitary elephant, but not for monkeys. The mirror test has attracted controversy among some researchers because it is entirely focused on vision, the primary sense in humans, while other species rely more heavily on other senses such as the olfactory sense in dogs.

A different approach to determine whether a non-human animal is conscious derives from passive speech research with a macaw (see Arielle). Some researchers propose that by passively listening to an animal's voluntary speech, it is possible to learn about the thoughts of another creature and to determine that the speaker is conscious. This type of research was originally used to investigate a child's crib speech by Weir (1962) and in investigations of early speech in children by Greenfield and others (1976). With speech-capable birds, the methods of passive-speech research open a new avenue for investigation.

See also

- Animal culture

- Animal cognition

- Animal sexual behaviour

- Animal tale

- Animal trial

- Anthropomorphism

- Herd behavior

- Mammal

- Non-human

- Stereotypes of animals

- Talking animals in fiction

- Ugly animal

- Zoomorphism

- Structures built by animals

- Tool use by animals